Tissue Release with a Spiky Ball

Jul 05, 2023

Spiky Balls are being seen more and more in shops and fitness studios, but what are they for and how do they work? Firstly, you need a good quality ball, some have shallower ‘spikes’ and a more forgiving surface, these are often referred to as ‘Pilates trigger point release spiky balls’ or ‘Prickle Stimulating Balls’. The texture and responsive surface of this type of spiky ball means that we can move into areas that intuitively feel of benefit, but we are able to move around, modulate and play with pressure and movement as simply feels right.

This is how these balls work on the myo-fascial system, the complex continuum of muscle and connective tissue (fascia) that creates the whole web of our bodies. Meeting this through the surface of the skin can help to reduce muscle tension, improve blood flow, increase body awareness and aid in injury prevention and rehabilitation. Loose fascia is a particular part of the superficial fascia, a web that from under the skin, moves into and between organs. One of its key qualities is to provide the quality of slide, aka slide-and-glide . A research paper on how connective tissue sliding works states, “Fascia can be divided into tissues that restrain motion, act as anchors for the skin, or provide lubrication and gliding.”

According to some texts , within the superficial fascia – the connective tissue web just beneath the skin - there is a vascular network independent of the lymphatic and blood pathways. It is called the Bonghan duct system, made of the same substance as fascia and believed to ease communication among all body areas (Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:961957 & Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:538350). This is currently being researched as potential for describing ancient meridian systems within the physical body (J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14(6):621–628 & J Acupunct Meridian Stud. 2009;2(2):93–106). This is where we can directly access and affect our body fluidity, with massage and using props in self-massage, such as a spiky ball where the soft ‘spikes’ can move into this layer.

All the fascial layers rely on a substance called hyaluronic acid to slide over each other, locally or out into the whole system (Surg Radiol Anat. 2011;33(10):891–896). There are some researchers who suggest strongly that any change in the viscoelasticity – ability for fluid movement - of the fascial system activates pain receptors . When tissues are dehydrated through lack or misdistribution of hyaluronic acid, the resulting viscosity can even become adhesive, altering the lines of forces within fascial layers. So not only can freeing these tissues allow tension release, but also how easily we are able to move.

This mechanism has been offered as one of the causes of stiffness and pain in the morning , more than joint issues so often blamed (Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2013;17(8):352). Tissue dehydration can occur at any time, but particularly overnight when we move are horizontal and move around much less. It can prevent the proper removal of what are often termed ‘toxins’, but are the bi-products of respiration; energy production within each cell. When they build-up, they have shown to stimulate pain receptors and create a more acid environment within cells (Surg Radiol Anat. 2011;33(10):891–896). A vicious cycle can ensue, where dysfunctional physiology of the hyaluronic acid complicates the sliding of the different fascial layers and once again pain receptors are stimulated. This occurs alongside the release of inflammatory neuropeptides, which has been associated with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME) (Front Physiol. 2013;4:115).

When tissues cannot easily slide, they show up as a fascial thickness under ultrasound, but not MMR (magnetic resonance imaging), so often overlooked and a possible root for chronic pain that is not easily identified . This densification can eventually become fibrosis, the thickening and scarring of connection tissue, which is known to be caused by a chronically inflammatory environment (such as Irritable Bowel Disorders or arthritis), stress, trauma, operations, injury and immobility .

Some simple self-massaging and exercise techniques with a spiky ball can not only help to free issues and ease pain, but also provide a time of self-care that feeds back into a sense of safety through the nervous system. This kind physical attention resonates through our entire beings and fosters a sense of well-being.

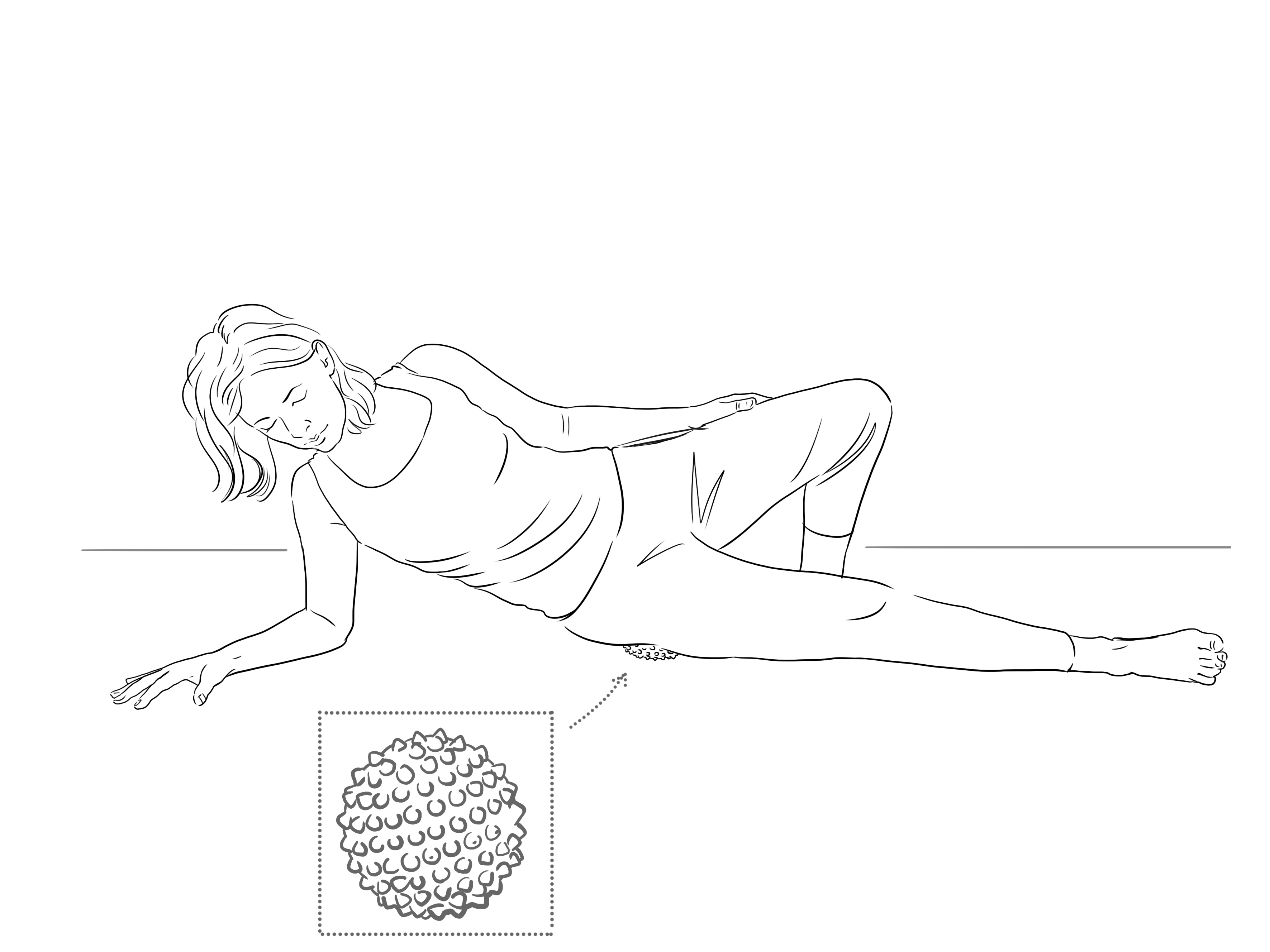

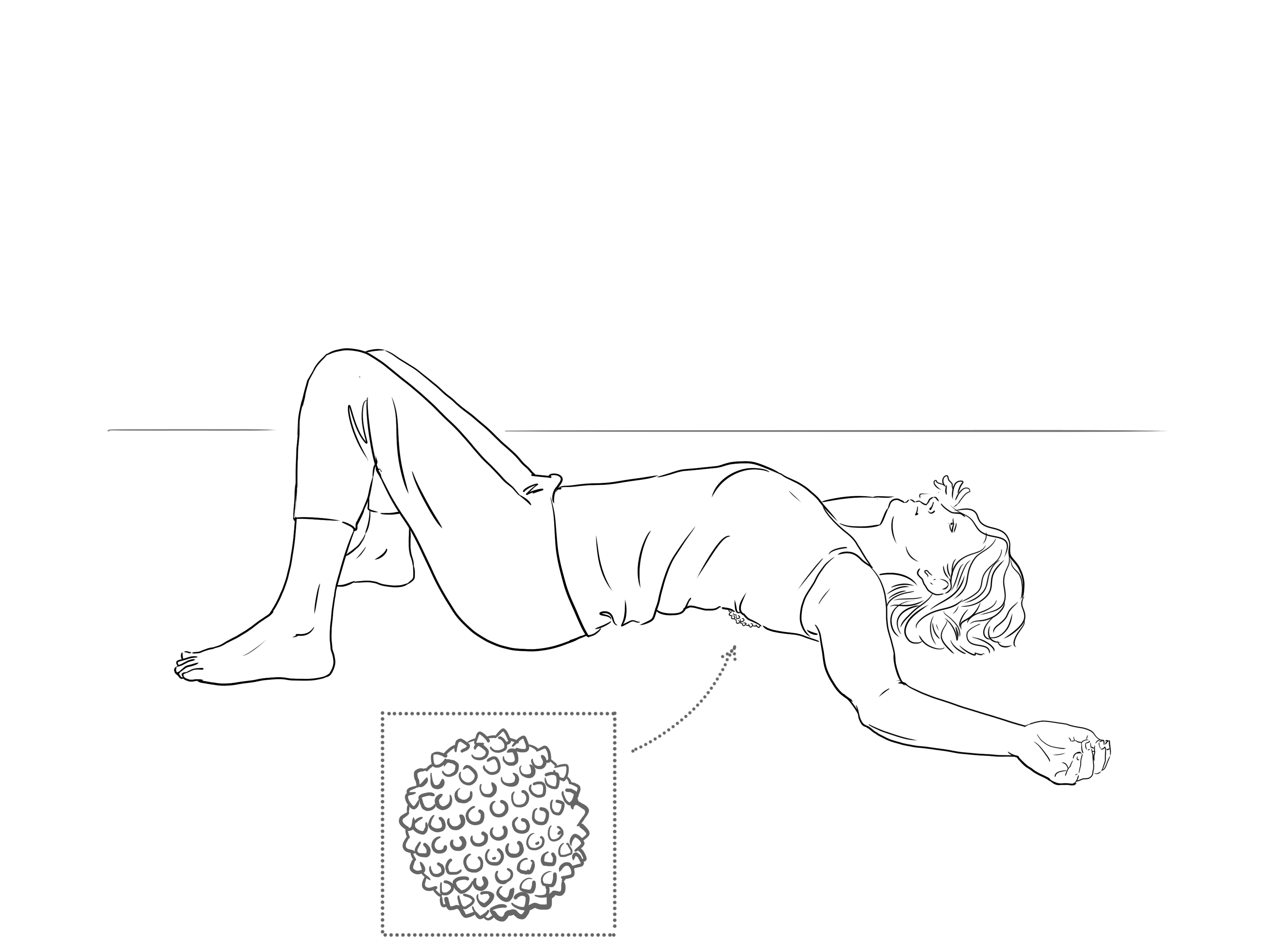

Outer thigh and IT band massage

Essentially you can self-massage any part of your body, you just start and play with movement and pressure. It will not always feel fully comfortable; meeting areas where they may be fascial tightness or a build-up of waste products may feel sore, but it will benefit, so focus on the sensation with full breath, coming in and out as feels right - you can build up over time. Massaging the outsides of the thighs (or IT bands) can be a particular area of tightness for those who run or cycle. You can reach this simply sitting or roll your weight over the ball as in fig.1.

As with all movements, avoid areas where there is broken skin, inflammation or bruising, but you can massage areas around to bring circulation there and promote healing.

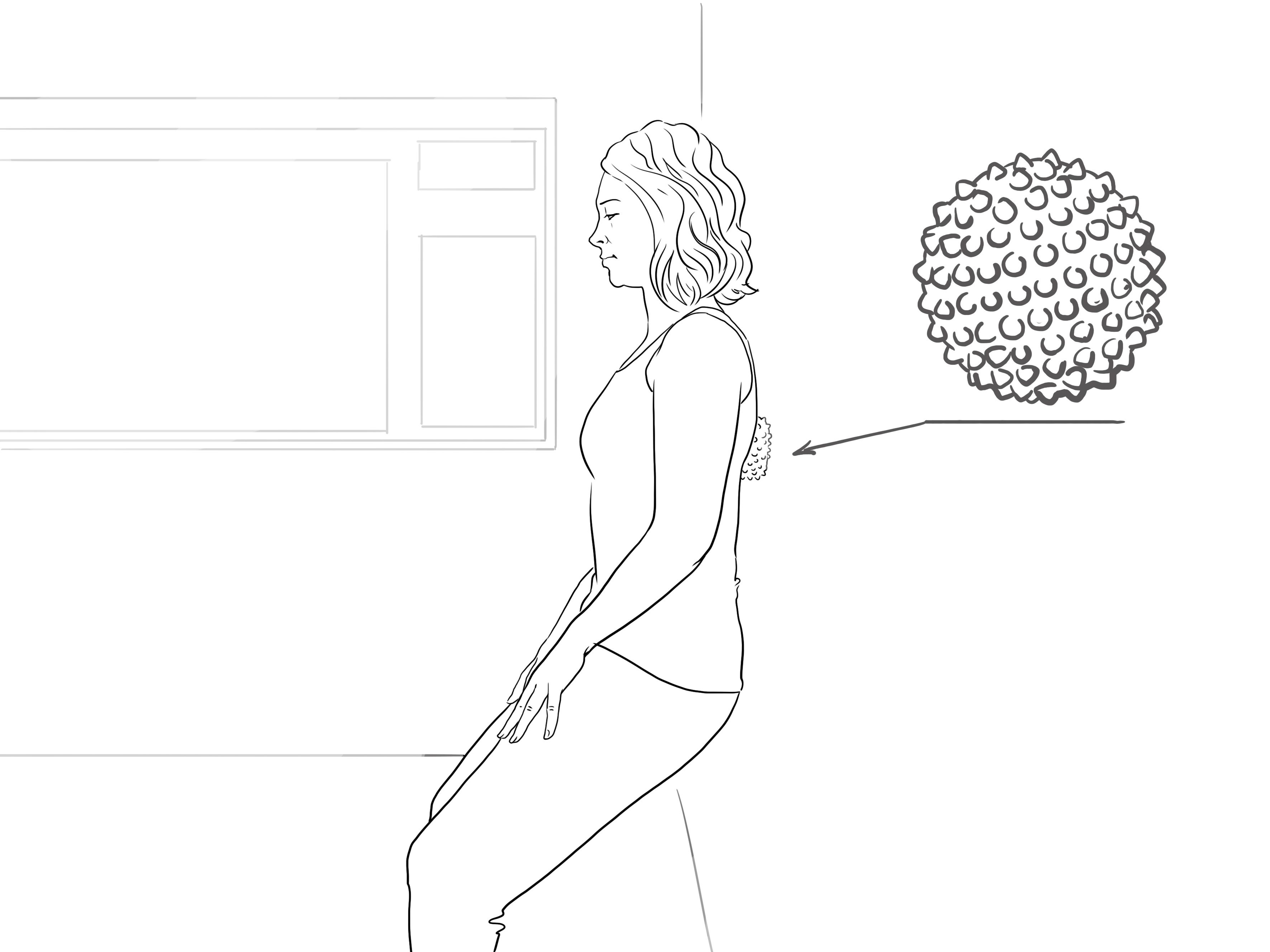

Rubbing between shoulders on a wall

Another common area of tension within modern postural habits is the upper back, as we often hunch over sitting on chairs or looking at technology. We can easily reach this area with the ball placed anywhere from between the shoulders upwards and move about the freely around on the wall.

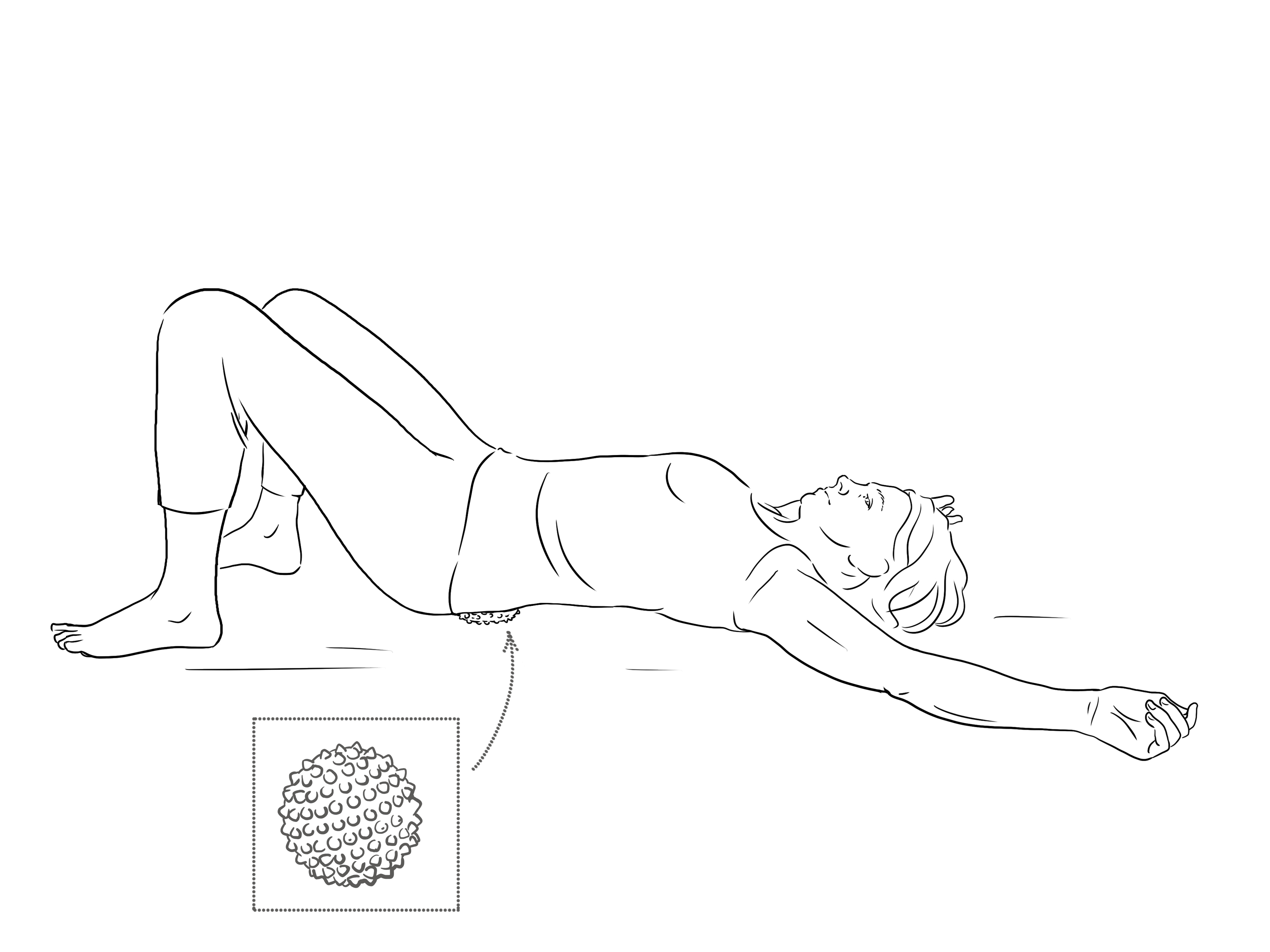

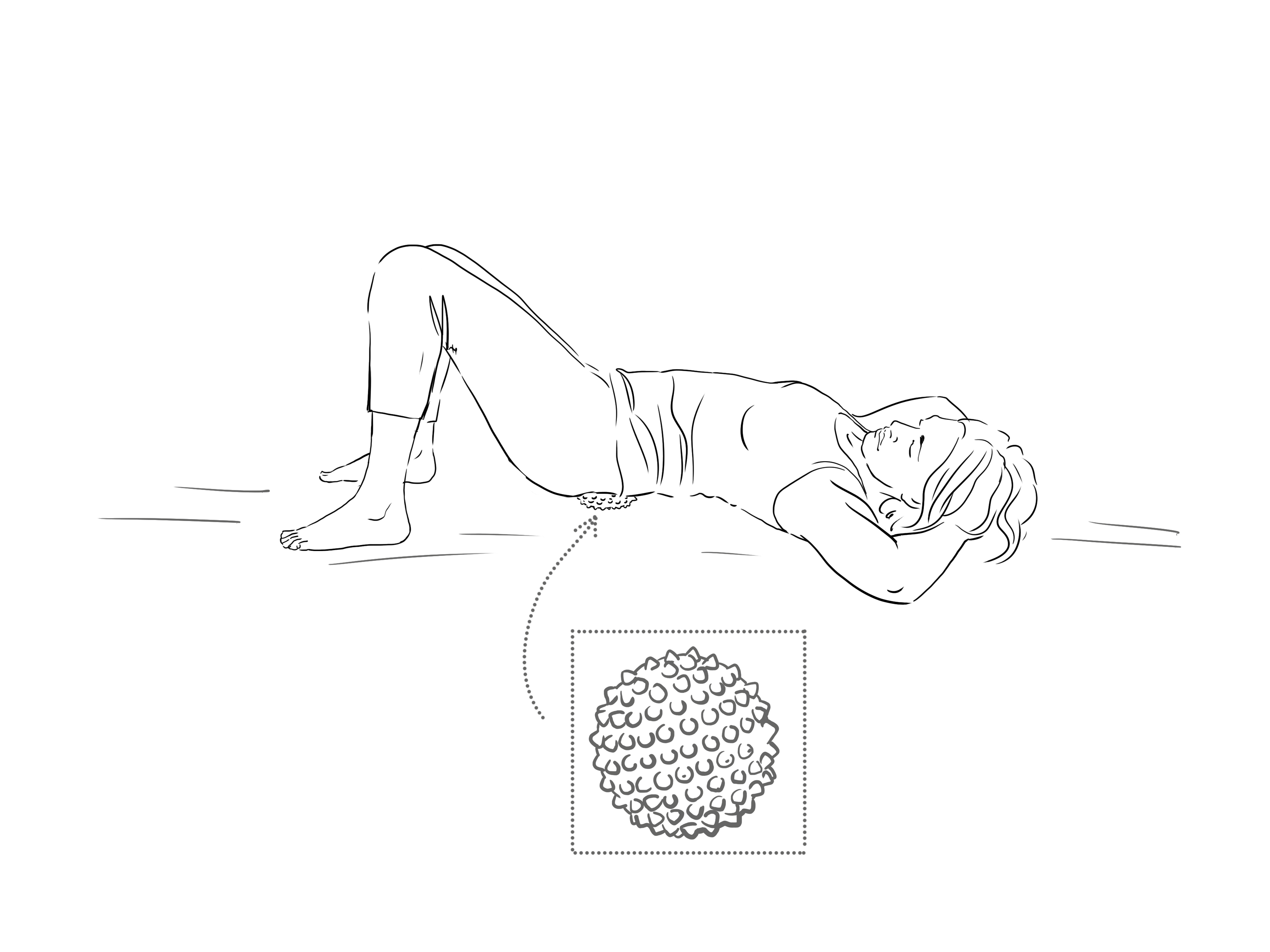

Under sacrum and buttocks

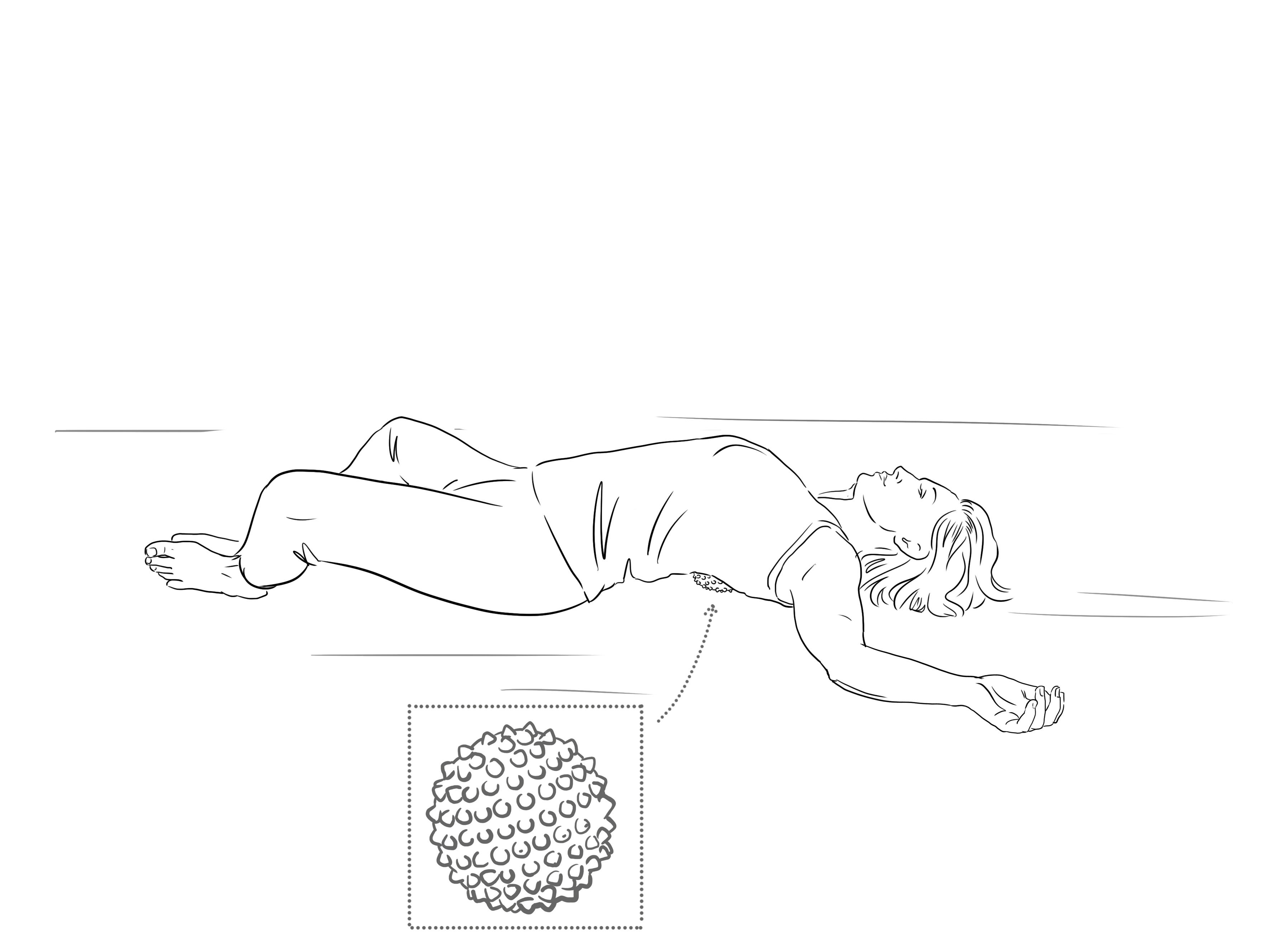

We can also use the floor for resistance to press our weight into, or when lying to let gravity give us a helping hand. Lying in Constructive Rest Position (CRP, fig.5) to start, with knees bent so the lower back is free to move and the psoas muscle (inside the hip bones) relaxed, place the ball underneath your sacrum, the large triangular bone that forms the back of your pelvis – between your waist and tailbone.

Spend some time just feeling how your breath moves you on the ball and accepting its presence and then explore any movements in any way that your body guides. You can move out to the sides, over to the buttocks and down to the tailbone too, all areas where we can store tension and can contribute to lower back pain. You can also interlink your fingers behind the base of your skull and include the rib cage, shoulders and neck, including a fish-like spine motion, moving your head and tailbone in the same direction to open out the opposite side of the body and swish from side-to-side (fig.6).

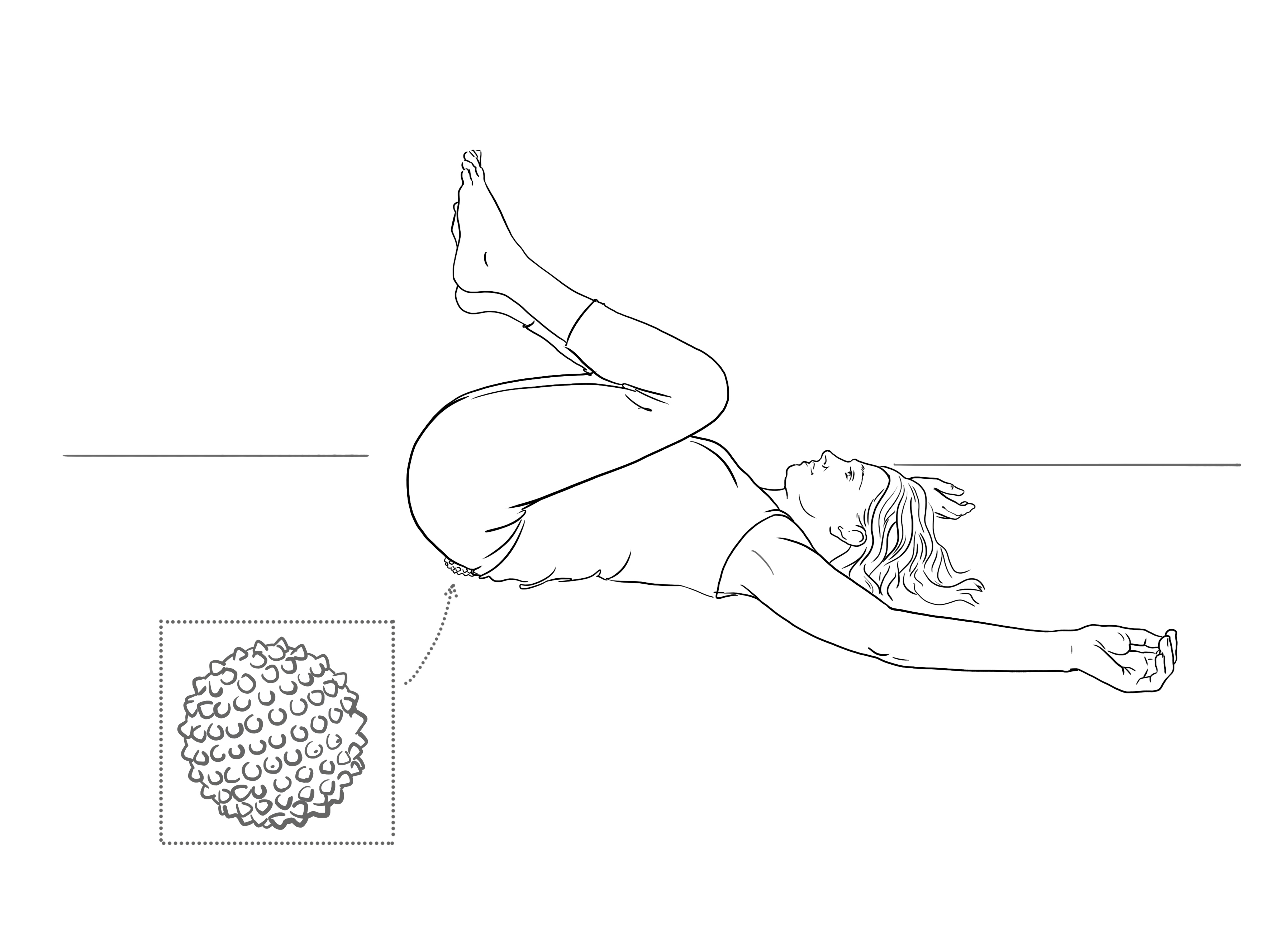

If it feels safe to do so, you can also draw the knees into the chest and add the weight of the legs and a curving of the lower back for a deeper effect (fig.7).

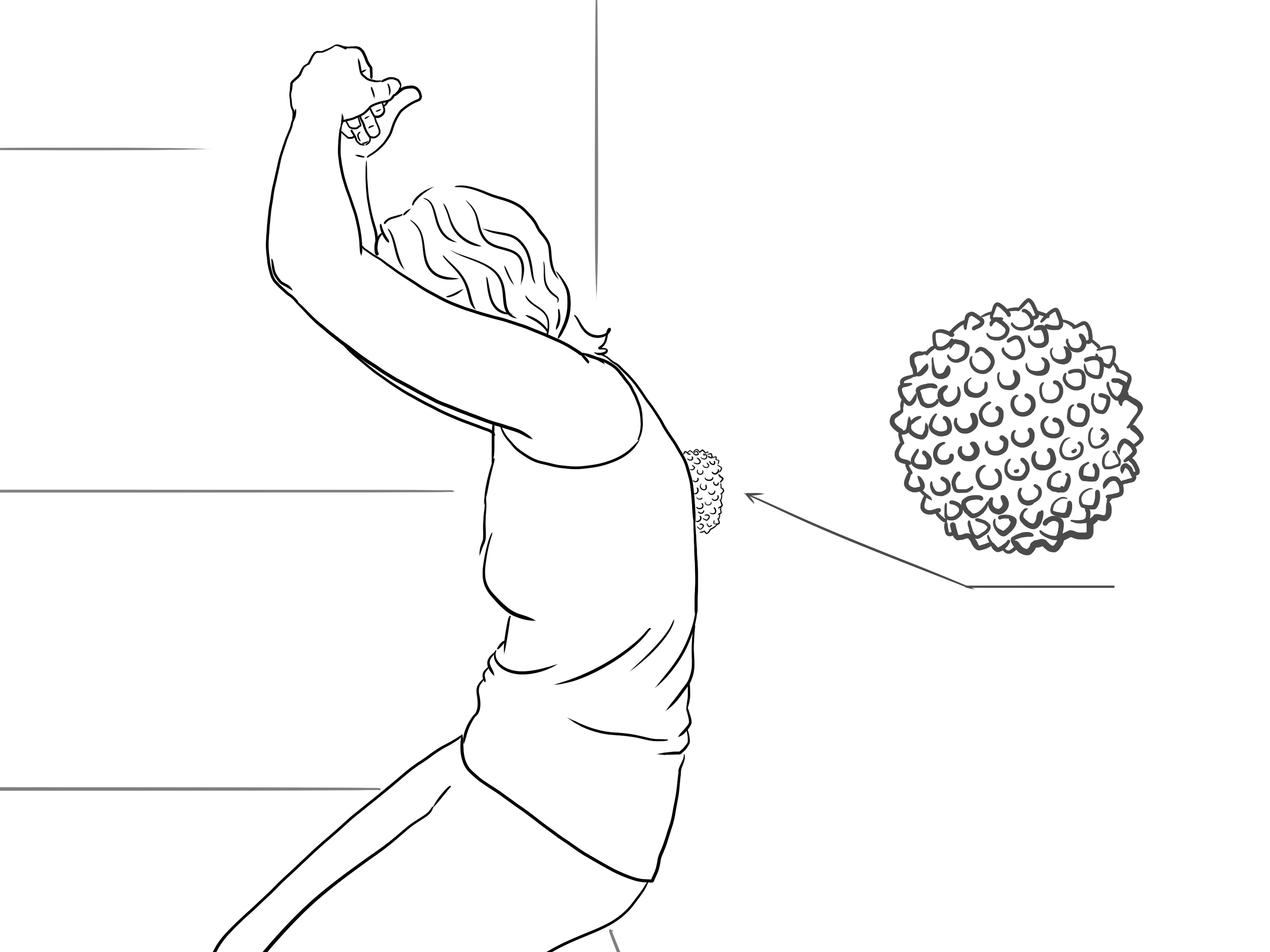

Into the upper back

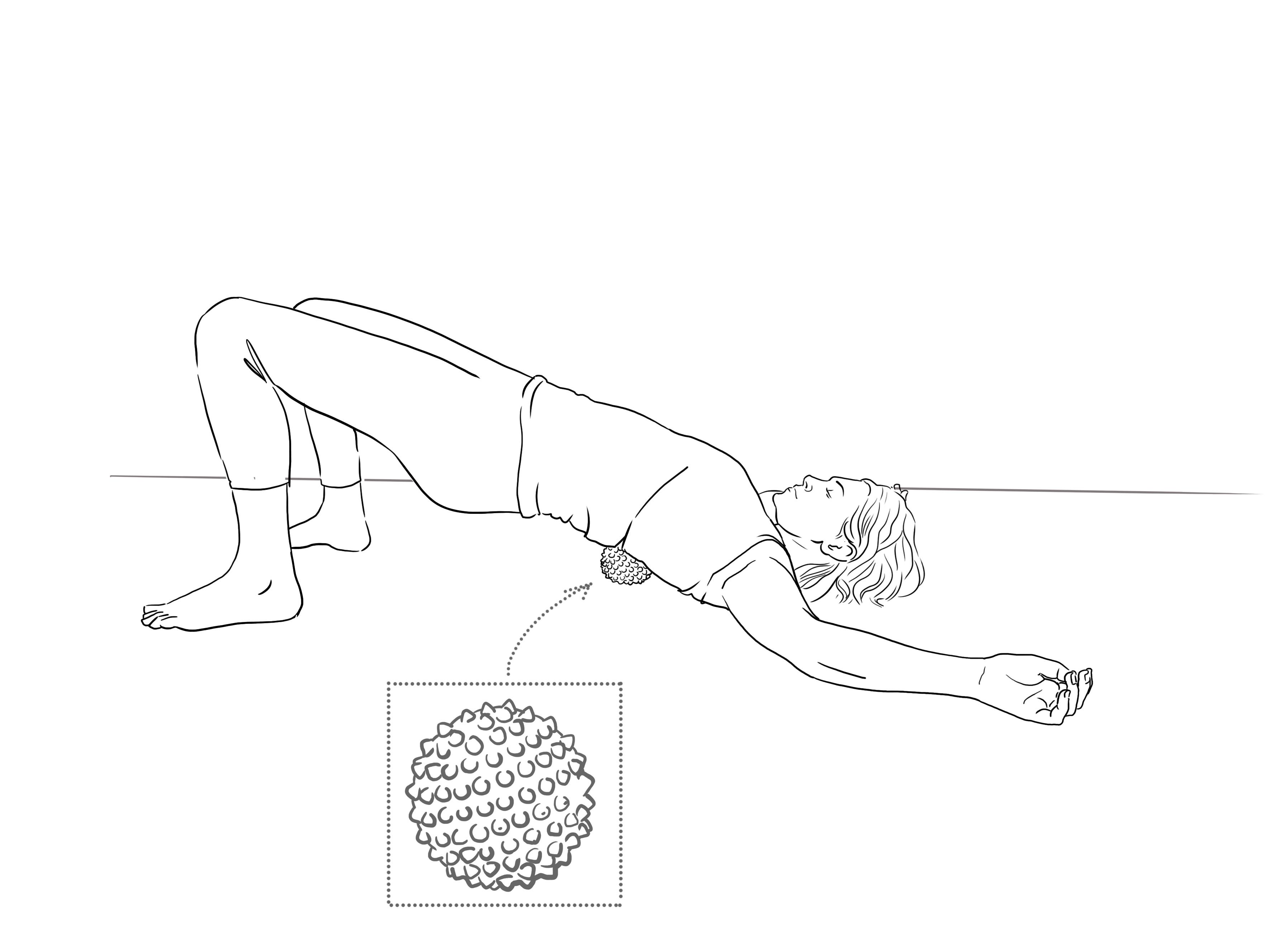

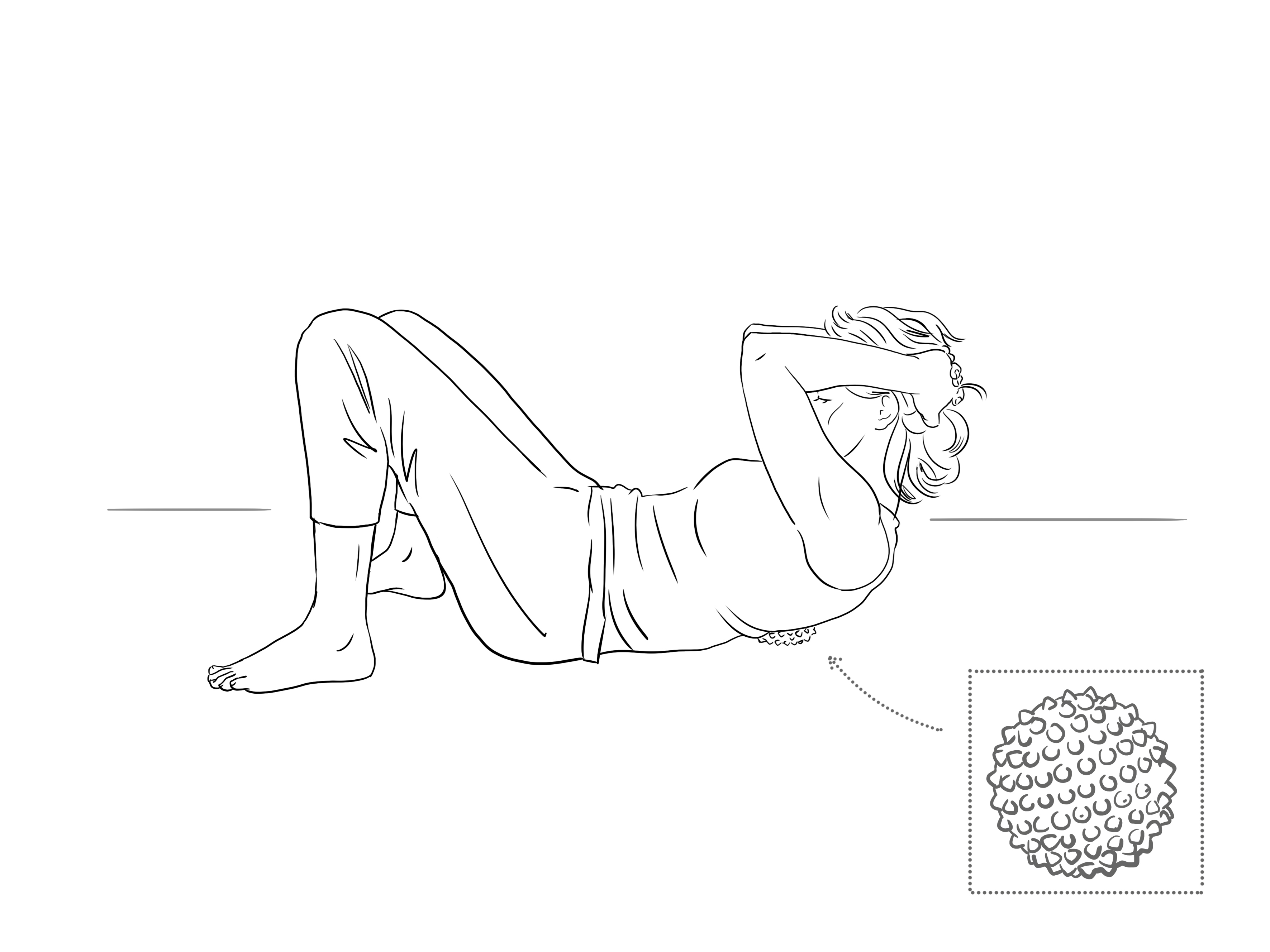

We can also move into the upper back with the weight of our bodies on the ground. From CRP, roll to one side to place the ball between the shoulder blades (fig.8) and taking the weight of the head with the hands on the back of the skull, soften the shoulders, eyes and jaw as you play around in this area, feeling into the nooks and crannies where we can get pretty ‘concrete’ in this area. When we are tight here and have less movement, the lower back can tend to take the strain instead.

Roll the head back down as you lift the hips, to come into a soft bridge pose with the ball opening the chest up from the back. You can simply breathe and hold here, feeling the ball’s support creating a body intelligence to be able to breathe up the front of the body and exhale down the back, or move and explore (fig.9).

If you feel open enough in the chest and it does not create any pinching into the lower back, you can slowly lower the hips down to the ground, or place a yoga block underneath if you need some height to be able to relax (fig.10). to create more space across the lower back here, you can walk the feet wider, turn the toes inwards and drop the knees together.

If your lower back is happy, then you can use the ball to come into a variation of the yoga pose Supta Baddha Konasana, (aka butterfly pose, fig.11) with the knees dropping out to the sides and soles of the feet together. You can place your feet as far away from your head as your lower back and hips need. It is always wise in this pose to find more length in the lower back with a prop, or the weight of the legs may simply jam the lumbar spine. In this modification, lifting the chest allows the lower spine to find more length and so we can soften into the groin as we let the breath flow freely.

Freeing the chest

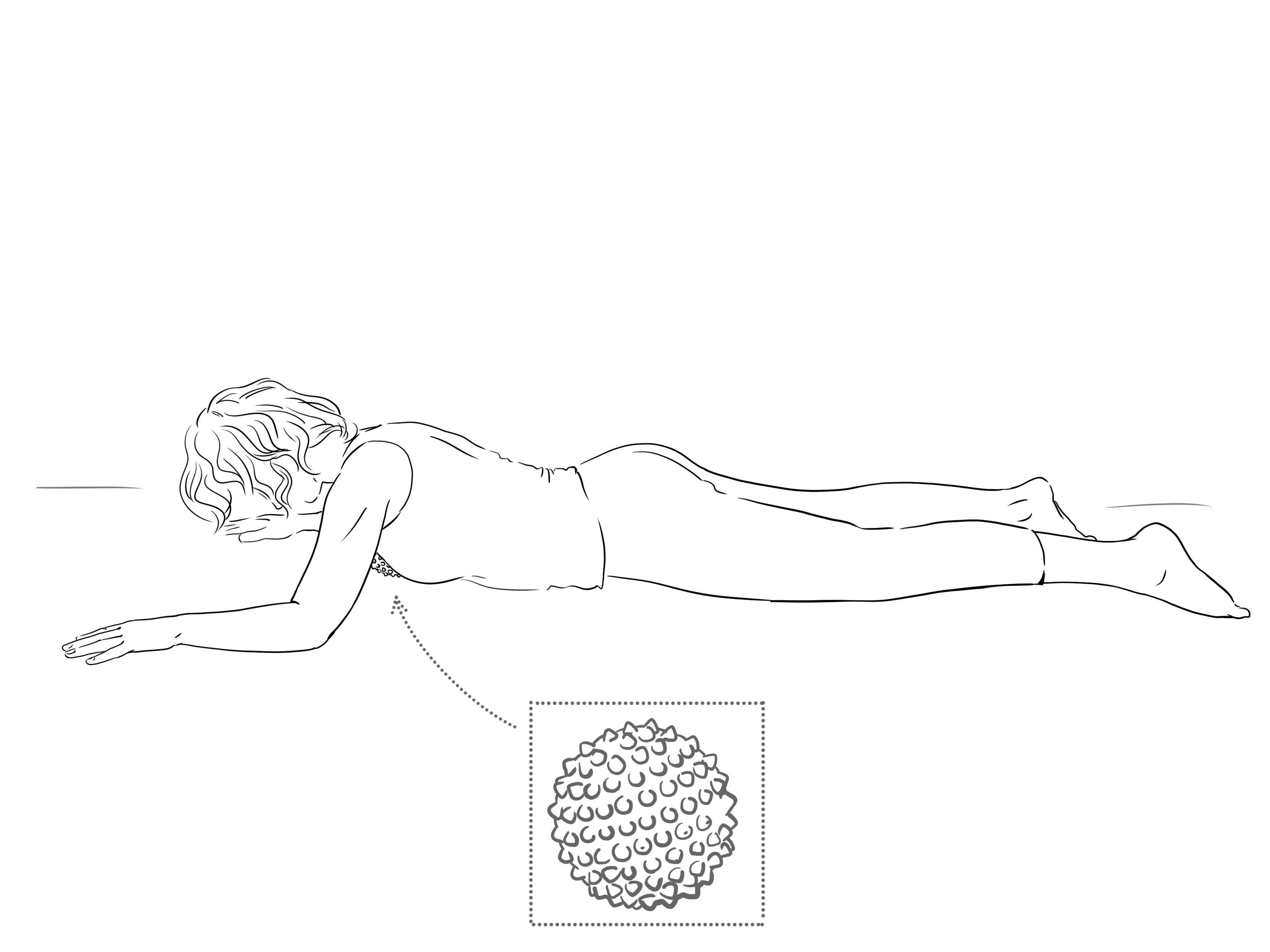

Coming onto your front, with legs as wide as your lower back needs to feel comfortable, come up onto your elbows, wider than your shoulders, placing the spiky ball under your breast bone; at about nipple height or where it feels most comfortable to able to lift the chest without jamming the lower back (fig.12).

Then you can let the ball take some of the work of the uplift through the chest as you open across the collarbones, feeling the myofascial release into the tissues of the chest where we can hold much tension. Let yourself breathe here to feel the natural motion of rise on the inhalation and dropping on the exhalation. As you become accustomed to the feelings of the ball here, you may even be able to drop the head down and increase weight onto this area, then raise the head to sit comfortably on the shoulders as you inhale (without jutting the chin forward) and drop down as you exhale.

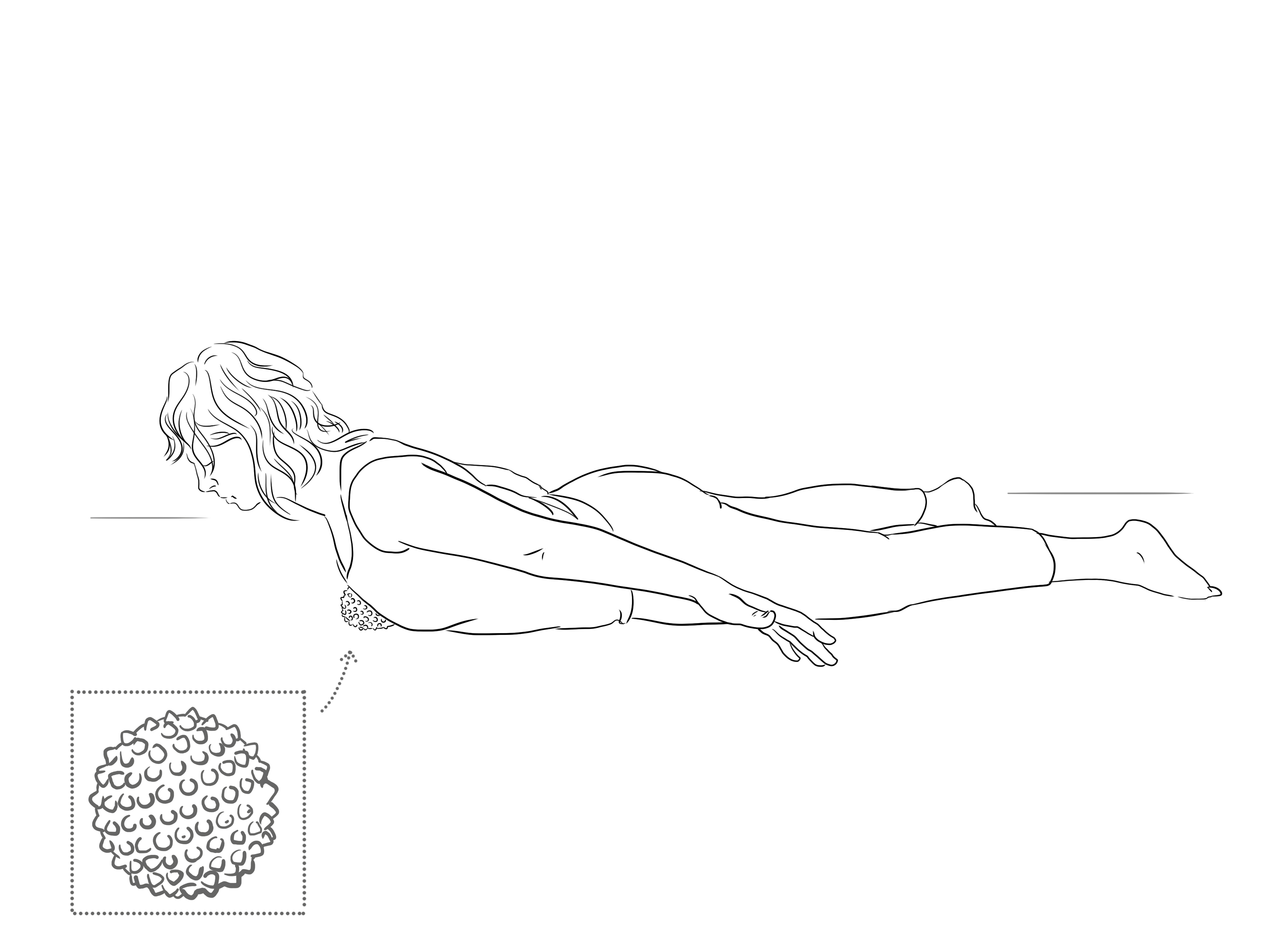

For a held position in a deeper backbend, then reach the arms out about 45 degrees away from your hips, palms facing down. Then lift the arms on an inhalation, keeping long in the sides and back of the neck (fig.13), feeling natural buoyancy as you breathe in and the lungs fill and a drop as they empty out on the exhale, giving a pulsing effect on the tissues.

After, simply lay down on the ground to let tissues release and let the after and ripple through and settle in. Alternately come to a downwards-facing dog position to lengthen the spine.

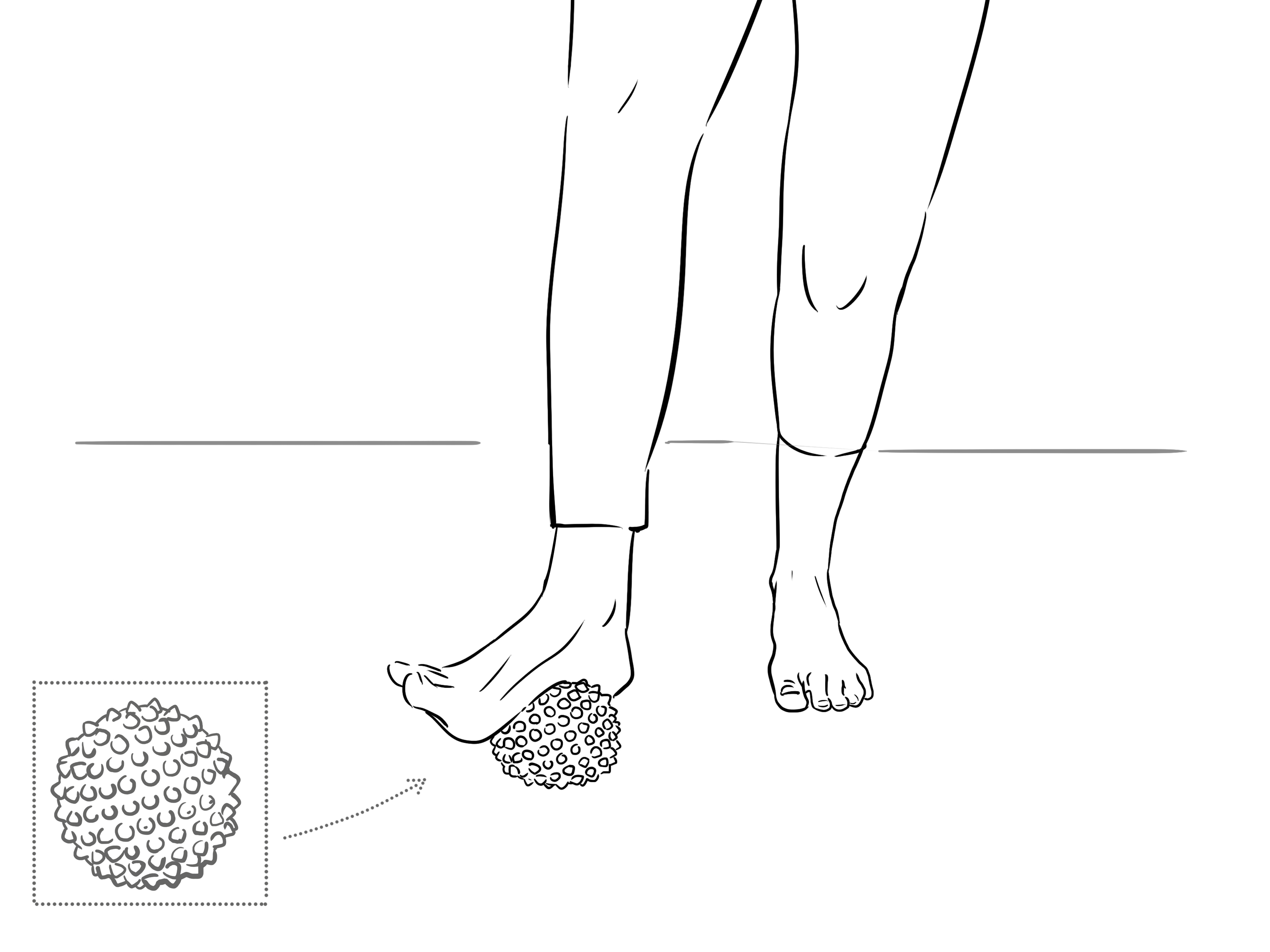

Releasing upright from the feet

Standing on one leg, holding onto a chair or to a wall if you need, roll one foot at a time over the spiky ball to fully explore every part of your foot for a good few minutes (fig.14). Include the heel, outside edge, particularly spending time on the instep, where the fascial lines begin from where we stand up through the inner legs and middle of the body.

Explore the different sensations and different pressures, even pushing down strongly into any region to create a deeper intensity and then easing off to feel flooding of fluids through the tissues as you release. Do each foot separately, standing and then walking between to feel the difference through each leg up from the ground. You may feel a sense of length and volume through the different sides, coming together after both feet are done.

When you walk and stand you may then feel that your legs seem longer as the fascial lines have more freedom up from the lower body into the torso. You can do this to help standing yoga practices, upright exercises such as lunges and running flow.

If you missed Charlotte's Natural Health Webinar on Fascia and Pain you can access the recording as a Whole Health member. Discover Whole Health with Charlotte here, featuring access to yoga classes, meditations, natural health webinars, supplement discounts and more...

(Stecco C, Stern R, Porzionato A, et al. Hyaluronan within fascia in the etiology of myofascial pain. Surg Radiol Anat. 2011;33(10):891–896. [PubMed])

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20571142/

- Li HY, Chen M, Yang JF, et al. Fluid flow along venous adventitia in rabbits: is it a potential drainage system complementary to vascular circulations? PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e41395. [PMC free article][PubMed]

- Lee BC, Yoon JW, Park SH, Yoon SZ. Toward a theory of the primo vascular system: a hypothetical circulatory system at the subcellular level. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:961957.[PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Li HY, Yang JF, Chen M, et al. Visualized regional hypodermic migration channels of interstitial fluid in human beings: are these ancient meridians? J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14(6):621–628. [PubMed]

- Park ES, Kim HY, Youn DH. The primo vascular structures alongside nervous system: its discovery and functional limitation. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:538350. [PMC free article][PubMed]

- Soh KS. Bonghan circulatory system as an extension of acupuncture meridians. J Acupunct Meridian Stud. 2009;2(2):93–106. [PubMed]

Stecco A, Gesi M, Stecco C, Stern R. Fascial components of the myofascial pain syndrome. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2013;17(8):352

Guimberteau JC, Delage JP, McGrouther DA, Wong JK. The microvacuolar system: how connective tissue sliding works. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2010;35(8):614–622

Stecco C, Stern R, Porzionato A, et al. Hyaluronan within fascia in the etiology of myofascial pain. Surg Radiol Anat. 2011;33(10):891–896

Rowe PC, Fontaine KR, Violand RL. Neuromuscular strain as a contributor to cognitive and other symptoms in chronic fatigue syndrome: hypothesis and conceptual model. Front Physiol.

Stecco A, Meneghini A, Stern R, Stecco C, Imamura M. Ultrasonography in myofascial neck pain: randomized clinical trial for diagnosis and follow-up. Surg Radiol Anat. 2014;36(3):243–253

Liptan GL. Fascia: A missing link in our understanding of the pathology of fibromyalgia. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2010;14(1):3–12.