The Benefits of Barefoot Running

Nov 18, 2021

Running without shoes or in shoes that allow us to feel the ground is part of a primal movement trend, where greater anthropological understanding has created a shift across many exercise systems. This return to physical activity that honours our inherent design has taken up a more natural approach to our bodies by many, but what is thinking and research behind it?

“Shoes do no more for the foot than a hat does for the brain.” - Dr. Mercer Rang, orthopaedic surgeon and researcher in paediatric development.

This subject came into public awareness in a big way following the release of Born to Run: The Hidden Tribe, the Ultra-Runners, and the Greatest Race the World Has Never Seen (Profile Books 2010), the best-selling book from journalist Christopher McDougall, who after years of repeated running injury, successfully changed his running style to model that of the reclusive Tarahuma Indian Tribe in the Mexican Copper Canyons. They run over 100 miles at a time, at incredible speeds, without the routine injuries of most modern runners. This lead to an investigation of the multi-billion-dollar sports shoe industry and debunking of many running myths, such as humans never ran on hard surfaces barefoot - in fact many ran (and still do) on sun-baked surfaces as hard as concrete.

McDougall states; "Only in our lifetime has running become associated with fear and injury. Do you think Geronimo worried about plantar fasciitis before setting off to run 50 miles across the stone-hard Mojave desert to steal horses?"

Douglass cites many other examples of running before the modern trainer was evented, such as Ramses II who had to legitimize his hold on the Ancient Egyptian throne every few years by performing a long-distance run, which he continued to do until he was over 90 years old. Still the Marathon Monks of Mt. Hiei in Japan run up to 50 miles a day in flimsy sandals for seven years.

Running injury is explained by many barefoot running proponents as being a matter of skill rather than a shoe correcting something wrong with our feet, when other animals run perfectly well without. The selling of more and more cushioned shoes simply allows poor technique that strains ankles, knees and hips to continue as there is no natural feedback of this shock and the need to respond and change.

The heel-to-toe foot-strike is commonly recommended by many a shoe salesman, but try doing this in bare feet on a hard surface and your body would soon ask you to stop.

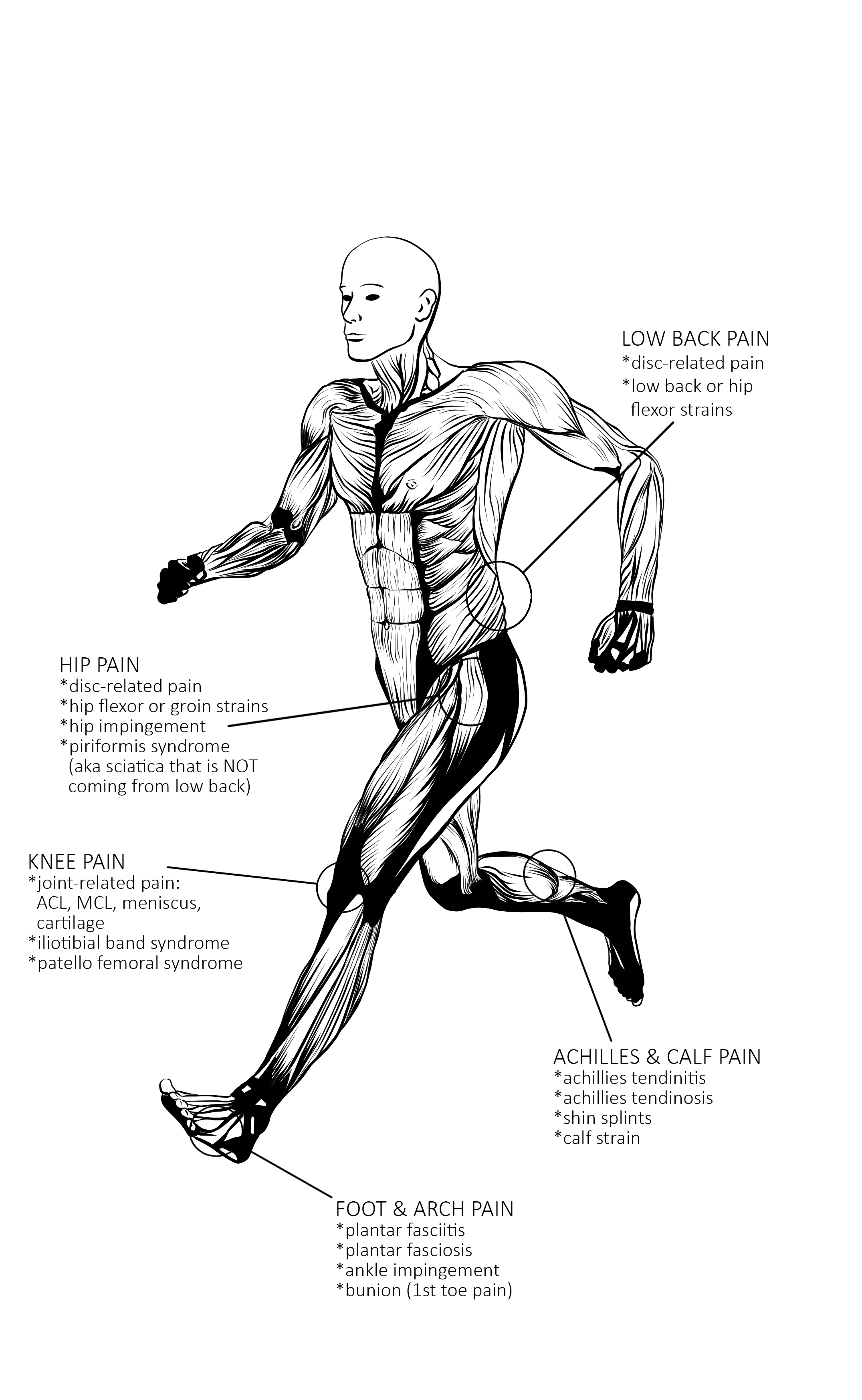

figure shows common injuries from ‘heel-strike’ running

Barefoot running isn't simply about doing it with no shoes, but going back to the thinner soles (‘minimalist shoes’) that allowed the feedback from the ground so necessary for a mindful relationship with our bodies ie one without injury. This involves changing the whole technique, foot to head, to alter the force transmission up from the ground at every part of the movement.

“We found pockets of people all over the globe who are still running barefoot, and what you find is that during propulsion and landing, they have far more range of motion in the foot and engage more of the toe. Their feet flex, spread, splay and grip the surface, meaning you have less pronation and more distribution of pressure.” - Jeff Pisciotta, Senior Researcher, Nike’s Sports Research Lab.

This subject is of particular interest to Dr Daniel Lieberman, a paleoanthropologist in the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University. In his book The Story of the Human Body: Evolution, Health, and Disease (Vintage, 2014), Lieberman describes how the human foot differs from that of our nearest primate cousins with our ability to harden the instep to take a forward step. This was necessary to allow the full forward bipedal step with feet under our hips, whilst our nearest flat-footed chimpanzee cousins sway side-to-side to walk upright and drop down to all-fours to run.

Such insights were partly a result of Lieberman and colleagues’ 2010 research paper into “Foot strike patterns and collision forces in habitually barefoot versus shod runners”, measuring the habits of those wearing modern running shoes with cushioned soles against no shoes or less built-up soles (Nature 2010;463:531–535) and stating:

“Humans have engaged in endurance running for millions of years, but the modern running shoe was not invented until the 1970s. For most of human evolutionary history, runners were either barefoot or wore minimal footwear such as sandals or moccasins with smaller heels and little cushioning relative to modern running shoes.”

Measuring how runners coped with the ground impact (with kinematic and kinetic analyses) before the invention of the modern shoe, their findings were that habitually barefoot endurance runners:

- Often land on the fore-foot (fore-foot strike) before bringing down the heel, but they sometimes land with a flat foot (mid-foot strike)

- They land on the heel less often (rear-foot strike).

- Even on hard surfaces, barefoot runners who fore-foot strike generate smaller collision forces than shod rear-foot strikers.

In contrast, those who habitually wear shoes to run:

- Mostly rear-foot strike, facilitated by the elevated and cushioned heel of the modern running shoe.

This difference, which translates up the whole body ripples up from a difference in the foot’s impact relationship to the ground, up through the whole body. This starts from the front-foot strike creating more plantar flexion in the foot. This is where it is more ‘pointed’, although the toes are not, so the sole of the foot is flexed – drawn in rather than extended. This decreases the effective mass of the body colliding with the ground and more ankle compliance ie less hard impact, protecting the feet and lower limbs from some of the impact-related injuries now experienced by a high percentage of runners.

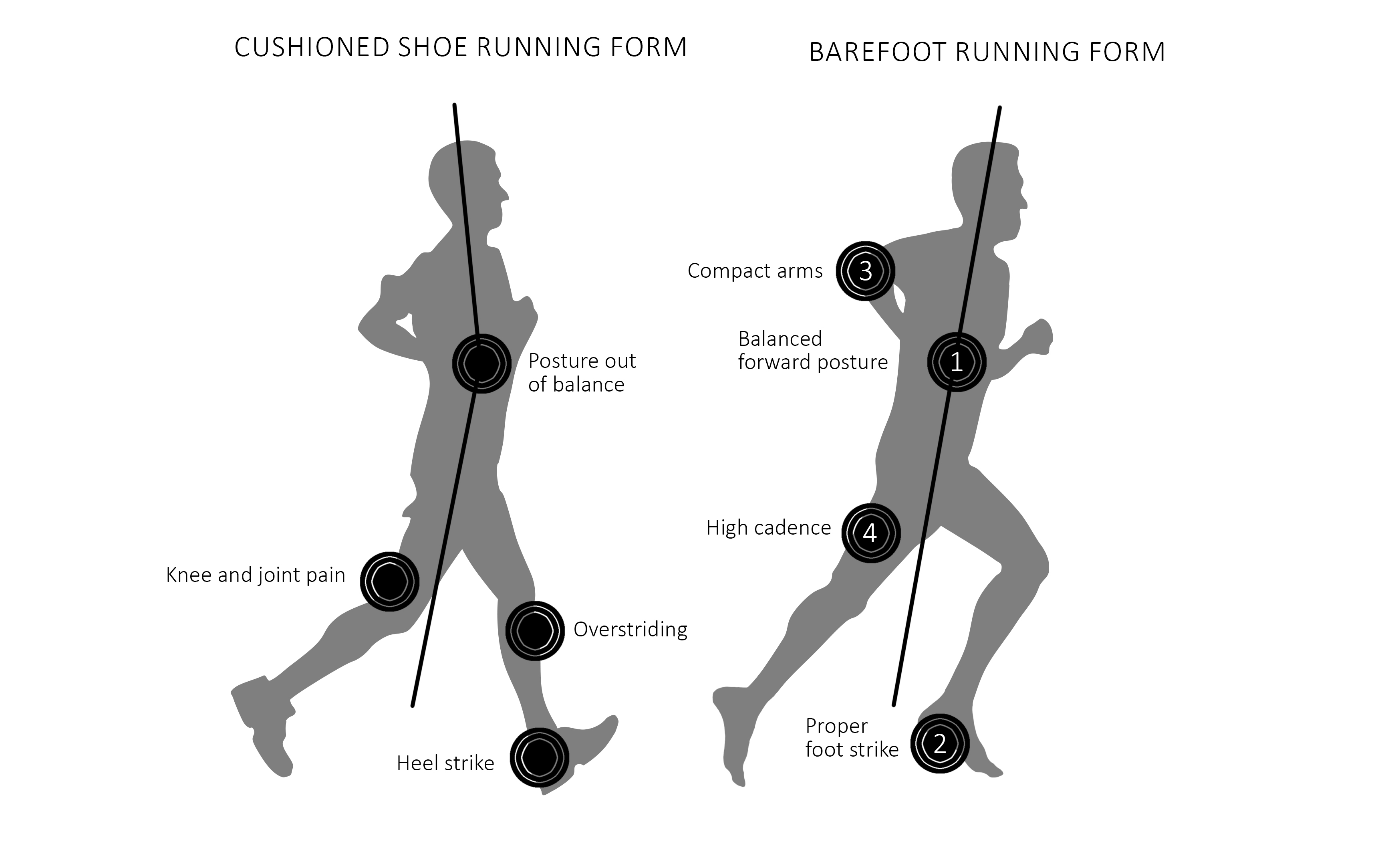

Figure shows differences in foot-to-ground contact between cushioned and ‘barefoot’ shoes

The average runner strikes the ground 600 times per kilometre, so runners are prone to repetitive stress injuries - simply cushioning the blow is not the answer, how we meet the ground is the key. Lieberman believes that while cushioned, high-heeled running shoes may be comfortable, they limit the amount one can feel the ground, meaning we are less likely to adapt to mitigate impact and easier to keep up a habit of landing on the heel. Barefoot running advocates say that cushioned shoes may weaken foot muscles (including arch strength) through reliance on arch supports and stiffened soles that take over the role of the foot. This weakness may then contribute to ‘excessive pronation’, where the foot rolls inwards and arches drop, as well as the inflammatory foot condition plantar fasciitis.

Not everyone is in agreement with this viewpoint, a recent review of the evidence (Revista Española de Podología 2016;27(1),e1-e3) reported that laboratory-based biomechanical studies showed a number of differences between barefoot and shod running, but almost all of these are just differences, with the variations not superior for barefoot running or linked changes in injury risk.

The review affirms the different load-bearing that the techniques involve and how there may be an adjustment period when moving from one to another, it concludes; “There is nothing wrong with barefoot running, provided that the tissues that have an increased load in them are given time to adapt to the loads and in some people that increase in loads may be too great. This also means that it has potential to help some runners by reducing the load in a problematic tissue. What is wrong with barefoot running is the claims that get made for it by those that promote it are not supported by the current understanding of the preponderance of the evidence.”

Although this review states that there is no evidence from ‘the field’ ie taken from running outside rather that inside in contrived conditions, a paper called Barefoot running survey: Evidence from the field reported back experiences of 509 runner completing a survey (Journal of Sport and Health Science 2014;3(2),131-136). Of these participants 93% of them incorporated some type of barefoot running into their weekly mileage, with 53% using it as a training tool to improve specific aspects of their running and 60% due to the promise of improved efficiency, 53% an attempt to get past injury and 52% responding to media hype.

A large majority (68%) of runners participating in this study did not suffer new injuries after starting barefoot running. In fact, most (69%) experienced relief of previous injuries; reporting improvement of running-related issues after switching to barefoot running, particularly of knee (46%), foot (19%), ankle (17%), hip (14%) and lower back (14%) – all significant results.

Barefoot running technique

There are four foundations of barefoot running (shown in figure above) that for many may be a whole relearning of technique, but worth the new body awareness this process of coming back to more relaxed and natural motion can bring:

- Balanced forward posture

With the forward propulsion of running, tipping forward makes sense. Barefoot running changes our balance so there can be a period of adjustment whilst you learn to stand tall and gaze forward in this new position, where you also keep the chest open and shoulders back and relaxed. Tipping forward allows the landing on the fore-foot or mid-foot for some.

- Safe and natural foot-strike

Landing softly with the knee bent, very different to a heel-strike where the leg may be almost to straight and the knee braced in position and over-striding (too long) tends to occur; you need to step your feet under you, not in front. With no shoes or minimalist soles, you allow your feet to be messengers and inform how you may need to modify your stance or technique. Lean a little from the ankles, pick up your feet, focus landing on the outer ball of your foot and your body will find its way.

- Compact arms

This stance naturally creates small and relaxed arm movements, close into the body, with movement more easily pushed back and allowed to recoil back forward, rather than swayed from side-to-side. This is an efficient, effortless movement that supports easy motion through the spine. The elbows only extend forward of the waist when sprinting.

- High cadence

Cadence is tempo and rhythm, hopefully the easy, natural stride we fall into, where elastic recoil through the fascia seems to happen effortlessly. With barefoot running this is often 170-180 steps per minute; a shorter stride without overextending. To find this, you can count 30 steps per leg in 20 seconds for a 180 cadence, feeling light, soft and quick foot placement.

This is attuning to mindfulness within running, so relaxed breath and listening to your body is the basis of non-injury; then you will naturally feel when you need to do less and recover, when you can push in further and not be lead by ambition, comparison to others or expectation. When you start, progress slowly as your body adapts to the change in force transmission. A few key pointers help to smooth this transition and connect into your natural and therefore efficient motion:

- The harder the surface the softer the landing

- Develop quick, springy feet that take over the bounce cushioned shoes provide

- Relax, breathe through the nose with full exhalations and enjoy!

The global athletic footwear market continues to grow and is projected to reach a value of USD 115.6 billion by 2023 (source: Wise Guy Reports). Recent sales figures put the sales of minimalist or barefoot running shoes (by companies such as Invivo and Vibram) at around 2–3% of the speciality running shoe market (Leisure Trends; personal communication, 2016), which could indicate that runners have lost interest in the trend, or otherwise reflect the success of the regular training shoe as both a skilfully marketing sports and fashion item. Whatever the trends may currently be, there is no substitute for experience – try getting more in touch with the ground, your body may well thank you!

Discover Whole Health with Charlotte here, featuring access to yoga classes, meditations, natural health webinars, including Charlotte's Natural Health Webinar on Feet, Grounding and Calm, and more...