Targeted Stretching for Different Exercises

Jan 20, 2022

Stretching can be something we look forward to or dread within our exercise regimens, so understanding its purpose and effects can create more depth and motivation, however we feel. Messages can be conflicting, so some simple basics can help us navigate confusion towards following your body’s needs.

Stretching for sports is not the same as in yoga; rather than looking to improve flexibility alone, static (still) stretching after exercise is designed to lengthen muscle shortened through use back to its normal range of motion (ROM). This is why dynamic (moving), rather than static is recommended for warm-ups. More flexibility ie more range through muscle and around joints may actually impede the action and strength of specific movements needed for sport.

We can’t actually lengthen muscle – this is already determined by its insertion and origin ie where it is attached and leads to in terms of bones and tendons – but we can lessen resistance to a stretch, where the nervous system doesn’t send pain signals to stop us doing it. The body adapts to the movements we make the most and if this is sitting on chairs, we can take that shape into our exercise posture. The stretches here take such modern issues into consideration.

Stretching goes beyond physical function – it also has a calming effect on the nervous system, with studies showing that our vagal tone or how effective we are at calming down and self-soothing, is heightened with regular stretching, leaving us more able to cope with challenges and to release muscles tensed in the fight-or-flight response (J Strength Cond Res., 2011; 1579–85).

Warm-ups that are great for any sport

Moving muscles suddenly from a cold standstill to heated activity is quite a shock if we don’t warm up first, especially if they’ve been contracted by stress. This lack of pliability may make injuring tissues more likely as they don’t have give and adaptability. A 2008 study of over a thousand female footballers who included a warm-up over a season were compared to several hundred who did not. They had fewer injuries, including traumatic and overuse and those they did suffer were less severe. Static stretching where we hold positions were not part of their warmup; muscles were moved continually in dynamic (moving or ‘active’) stretching (BMJ, 2008; 2469).

Static pre-exercise stretching may even reduce muscle strength during training. This is an area with much debate in the fitness world, with many abandoning the pre-workout stretch for good. For those who feel this is part of their routine and works for them, one study advises a quality rather than quantity approach, stating; “The detrimental effects of static stretch are mainly limited to longer durations (over 60 seconds) which may not be typically used during pre-exercise routines in clinical, healthy or athletic populations. Shorter durations of stretch (under 60 seconds) can be performed in a pre-exercise routine without compromising maximal muscle performance.” (Med Sci Sports Exerc., 2012; :154-64).

Static stretches work for after exercising when muscle is already pliable, but can create more pull onto tendons when performed from ‘cold’. In a 2013 meta-analysis of 104 studies called “Does pre-exercise static stretching inhibit maximal muscular performance?”, strength, power, and performance were shown to suffer with stretches over 45 seconds, regardless of age, gender or fitness. The researchers concluded that static stretching alone before exercise should generally be avoided (Scand J Med Sci Sports., 2013; 131-48).

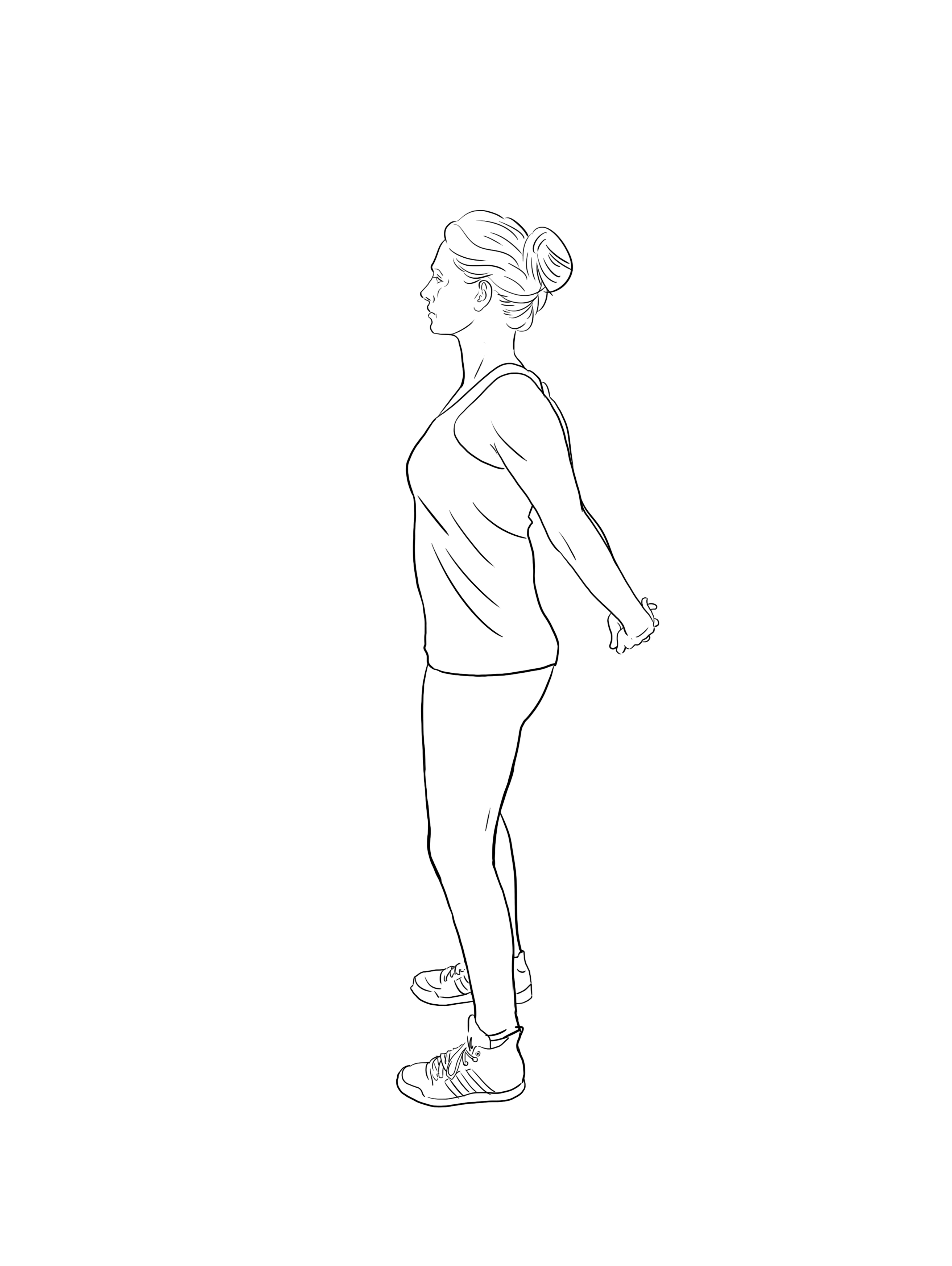

Active Stretching for Warm-up

These warm-up suggestions involve forms of dynamic (moving or ‘active’) stretching as might be used in Qi Gong or T’ai Chi – not hectic or forceful, as the word ‘dynamic’ often gets interpreted, but rather gentle, slow and purposeful movements that stay within a comfortable and natural range of movement. They help us regain that which may get lost through stress and negative postural habits, to exercise with more ease and supportive posture; loosening and activating muscles. Where movement follows a gentler version of the exercise you’re about to do it can warm up appropriate muscles best – anything that raises the heartbeat moderately and uses major muscle groups, like squatting or stair walking are also effective.

Try this sequence to help move through areas where we can tend to hold stress in the body:

• Move the jaw and face around to release any tightness there that can ripple down to stress in the rest of the body below.

• Roll the shoulders backwards and then forwards to free any tension held there.

• Lift and wave one arm back at a time in the air (like back stroke in swimming) and then forward (like the front crawl) to free motion through the shoulders, ribs and neck.

• Roll the head forward past the breastbone in semi-circles, up to each shoulder and back again to release constriction we commonly hold in the upper back, neck and shoulders from desk work.

• Swinging one leg at a time backwards and forwards through the range of motion we use for walking – this uses the eight of the leg to warm and lubricate the hip joints.

• Lift one bent knee at a time to rotate the thigh bone into the hip socket, use a wall or chair to support if needed.

• Rotate the ankles in big circles one way and then the other, then point and flex the feet to create flexibility where we hold ourselves up from the ground; particularly important if you’ve been sitting for long periods, wearing high heels or uncomfortable shoes.

Static Stretching After Workouts

We may be receiving conflicting messages about the validity of post-exercise stretching, but this seems to depend on what you might be stretching for. For those who feel that exercise compounds the lowered ROM we can get from modern sedentary living, the good news is that several review studies show that stretching does increase flexibility, which for many of us may seem intuitively and experientially true without the evidence. One review of studies totalling 1338 participants concluded that “the evidence appears to indicate that hamstring stretching increases ROM with a variety of stretching techniques, positions, and durations” (J Orthop Sports Phys Ther., 2005; 377–387). Another showed that calf muscle stretching increases ankle dorsiflexion (drawing the toes towards the shins), particularly when performed for over 30 minutes’ total stretching duration and so offering ease in a usual function we rely on for every day movement (Br J Sports Med., 2006; 870-5).

The debates come around injury risk and delayed onset muscle soreness prevention, with one review pooling five studies (77 subjects) implying that stretching reduces soreness in the 72 hours after exercising by, on average, only less than 2 mm on a 100 mm scale. They commented that athletes may consider these effects too small to make preventative stretching part of their routine. Results of two studies showed that stretching decreased the injury risk by only 5%, which they deemed statistically non-significant (BMJ 2002; 468).

The mechanisms of stretching are still not fully understood, which is at the heart of the debate “to stretch or not to stretch” after a workout. Whilst many report no physical changes whether they do, or not, others find this wind-down a key part of their routine and are happy for this to be neurological and psychological as much as muscular. Increased ROM is often the reason many come back – that they feel less able to function physically ‘normally’ without a post-exercise stretch.

A 2014 set out to investigate the influence of a six-week static stretching training programme on the structural and functional parameters of the human gastrocnemius medialis (calf) muscle and the Achilles tendon. These are areas where people can feel much tension, compounded by hours of sitting on chairs. Forty-nine volunteers were randomly assigned into static stretching and control groups; those stretching showed increased ROM that could not be explained by the structural changes in the muscle-tendon unit. The researchers concluded that it was likely due to “increased stretch tolerance possibly due to adaptations of nociceptive nerve endings” (Clin Biomech., 2014; 636-42). This is where a change in sensation rather than in the behaviour of muscle tissue is affected – so yes, stretching increases flexibility, but this might be due to our ability to tolerate the sensations rather than the physical motion itself (Phys Ther., 2010; 438-49).

When and how to stretch?

Immediately after exercise is a great window to stretch as you can view it as part of the programme, but muscles will still be warm within an hour. If that’s not possible, you will still get benefits doing them the same evening as your workout; anything that encourages general openness of body tissues supports your body movement and recovery. Trying to do too many means we’re much more likely to miss them out, whilst a few targeted stretches can help keep you pliable and with full ROM. You’re also more likely to execute them with more patience, care and mindfulness, rather than rush through them in a less conscious manner.

Professional athletes may be doing as many as three sides on each side (where appropriate), held for 30-90 seconds for static stretches, so at least 30 seconds once is a good minimum, building up to more as your exercise amount and rate increases. However, (once again) advice differs, with Brad Walker, author of Anatomy of Stretching saying, “A minimum hold of about 20 seconds is required for the muscle to relax and start to lengthen, while diminishing returns are experienced after 45-60 seconds.”

Breathing fully, allowing your breath to calm on the exhalation, sends signals to muscle spindles deep inside your muscles that regulate if it’s safe to let go and allow a stretch to occur. Pushing in or trying to force a stretch is counter-productive. Some muscles can take a while to accept that they can let go of protective constriction, especially if you’re still in the excitatory mode of high activity. Stretching can be part of coming down and moving into a phase where muscle can rebuild and come back stronger. Our bodies need to be able to rest for that strengthening recovery to happen, so consciously observing your breath settling down can have a deep, beneficial effect into your stretching.

General stretches - good for any sport and for walking or hiking

Stretching the inner thighs or adductors is a motion we may do very little in modern life and should be included in any sequence and after a long walk to counter all that forward motion, as they more of an opening effect through the groin. Even spending more time sitting on the ground, cross-legged as our we would have done before chairs came along, can help create space there that can take less tension into exercise. A more passive, sitting stance can get deeper into the hips and buttocks as they don’t need to work to hold us there. Standing versions offer the space to move and explore any helpful movement we may need, alongside a static stretch.

Hip openers

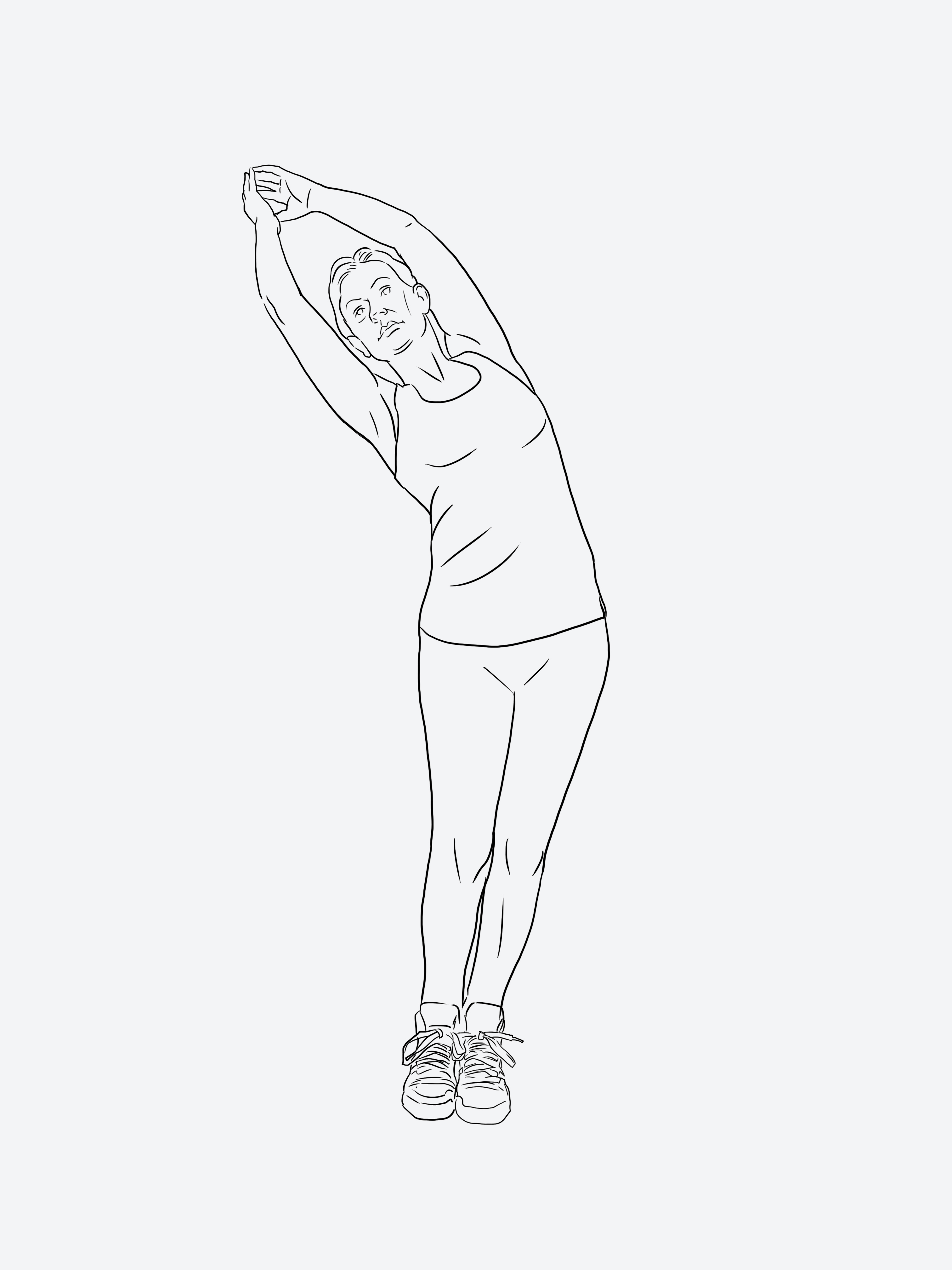

Opening into the side body can help open up between the ribs where we may hunch down over a desk and impair full breathing. This is useful if you feel you take a hunched position into exercise.

Standing lateral side stretch

Opening the backs of the feet and toes is often overlooked, but is the flexible foundation that supports us from the ground. Stuffing feet into shoes and walking less than we’re designed for means they can miss out on the natural kneading motion that is part of their structural health.

Stretches post-running

The repetitive forward-back motion of running can cause havoc on the lower back, especially when mixed in with a heavy dose of collapsing into this lumbar spine sitting for long periods on chairs. This motion can be done standing or lying, where bringing one leg into the chest at a time can help you explore the different needs of each side of your pelvis and back. Then knees in together lying down can be a helpful, restorative place to stay and let gravity do its work with the breath.

Standing knee-to-chest stretch

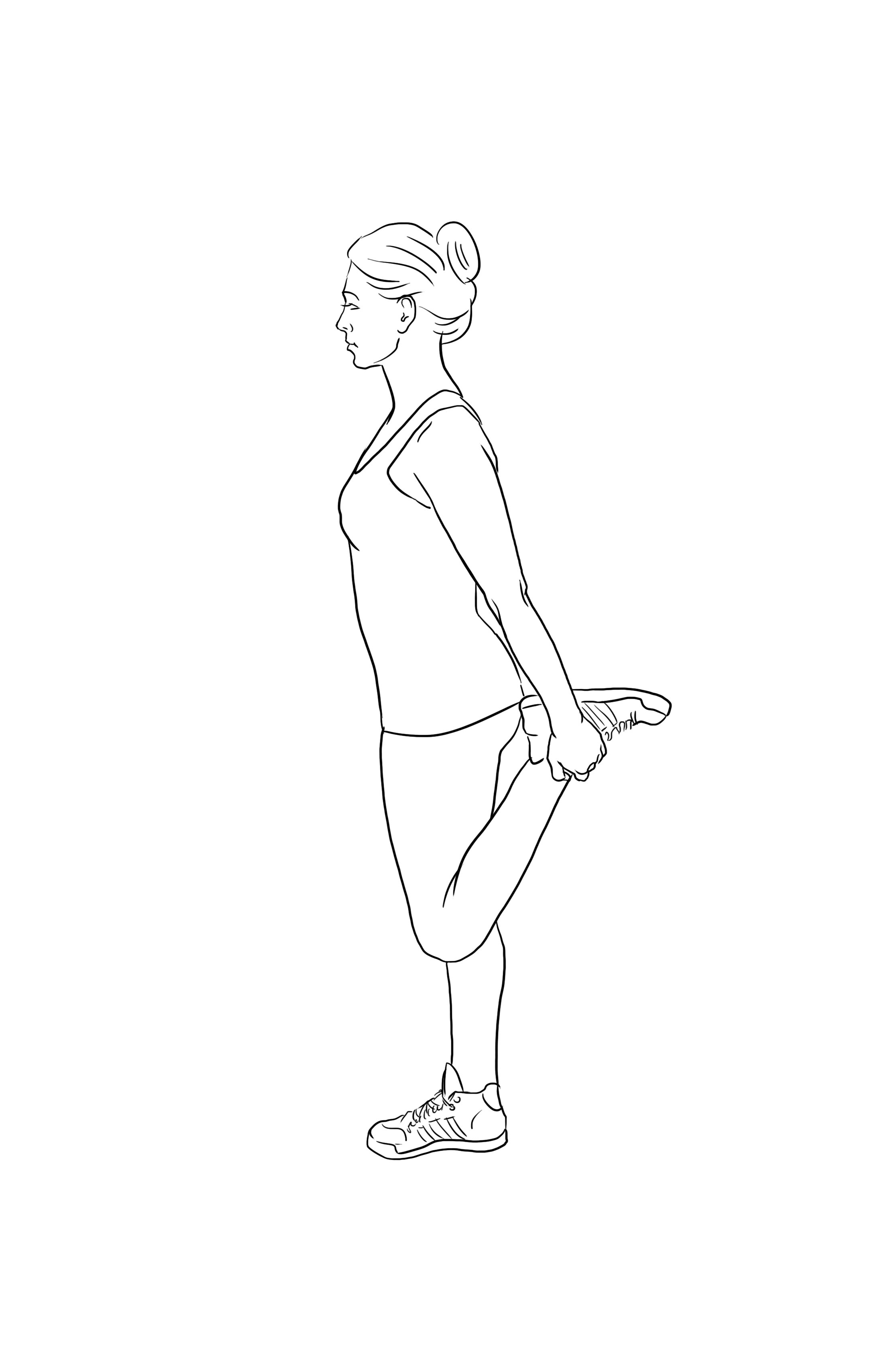

The opposite motion is to open the front body and fronts of the thighs after contracting them to bring the legs in towards the chest to take forward motion. Again, this is also supportive for sitting habits, which impede our ability to stand up fully through the psoas muscle that joins top and bottom body.

Kneeling quad stretch

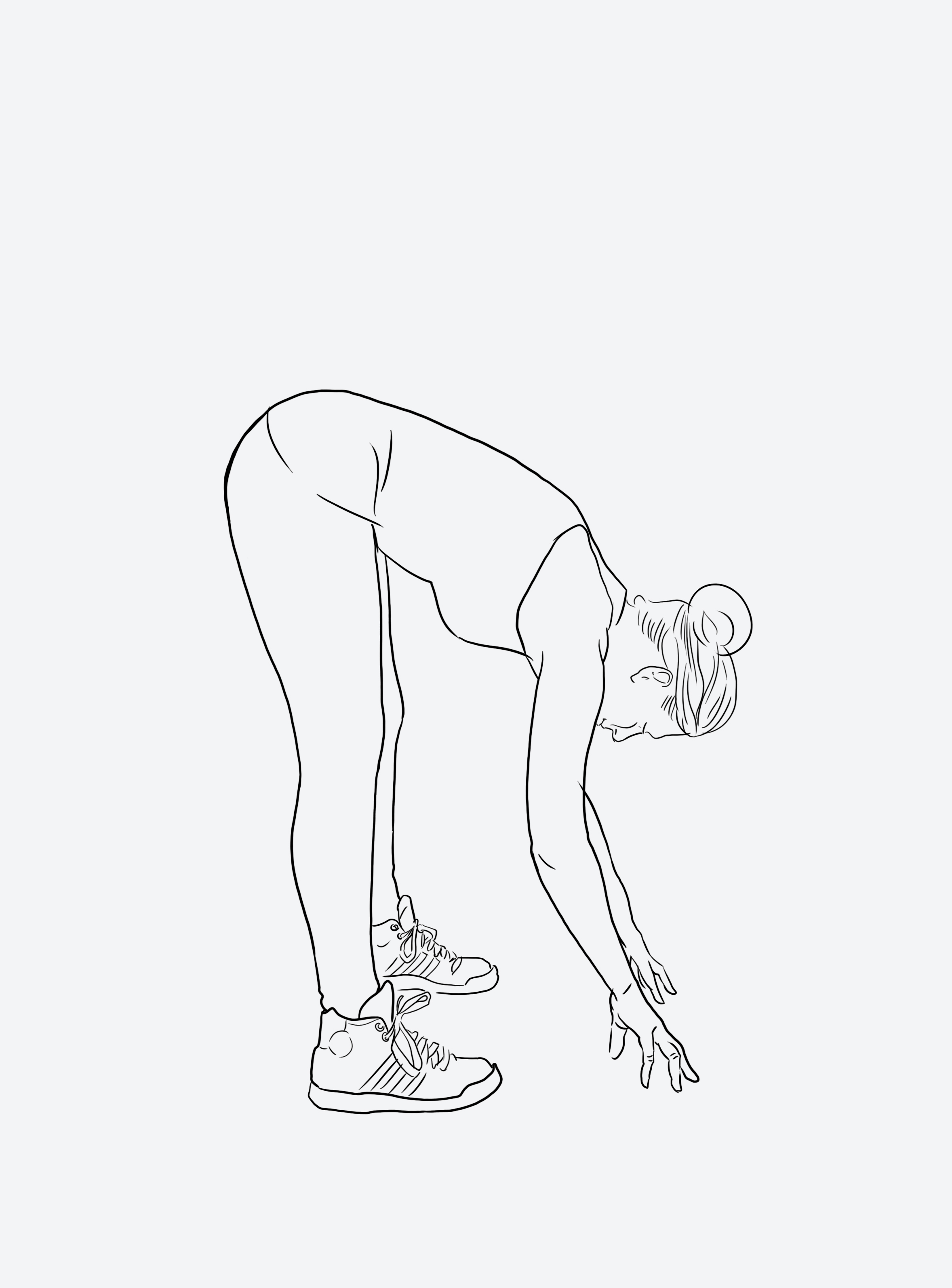

The calves work extremely hard for propulsion in running and time spent stretching them pays forward into how we move. If you have more flexibility, you can move into a full forward bend (see Standing reach down hamstring stretch in cycling) or even cross one foot over the other and bend down, to include a stretch in the iliotibial band, the long tendon down the outside of the thighs.

Standing toe-raised hamstring stretch

Combining the stretches for cycling and running covers the whole leg, hip and lower back areas that create most effort in these sports.

Cycling stretches

If you spend a lot of time sitting at a desk or on a chair, then compound that drawing your knees up into your chest movement (flexion) through cycling, you might develop tightness in the hip flexors – the muscles that perform this action.

Standing quad stretch

When hamstrings are tight, this limits ability to get lower down on the bike into a more aerodynamic position. If you are a more leisurely rider, this may not be a priority for you, but tight hamstrings can also limit our ability to ride for long periods of time. Also, not creating length at the backs of the thighs can contribute to and exacerbate lower back issues. You can also do the version for runners in Standing toe-raised hamstring stretch or bring your arms to a wall or chair if reaching for the ground isn’t accessible or strains your lower back.

Standing reach down hamstring stretch

Cycling, like running is a predominantly forward and back motion, with little outward rotation at the hips, but lots of action in the glutes (buttock muscles) that oppose and work with the hip flexors. Opening the hips and stretching around the back of the buttocks – including the piriformis muscle that can tight to get tight in cyclists and runners – can feel deep, but breathe fully to stay relaxed through the intensity. For those with more flexibility and yoga knowledge, pigeon pose is a deeper alternative.

Standing leg resting buttocks stretch

Racket sports (tennis, badminton, squash etc)

Reverse shoulder stretch

Here you open the front of the shoulders (deltoid muscle) countering the forward motion with a racquet. This is also a great at-a-desk stretch to open the top of the chest when this area becomes constricted.

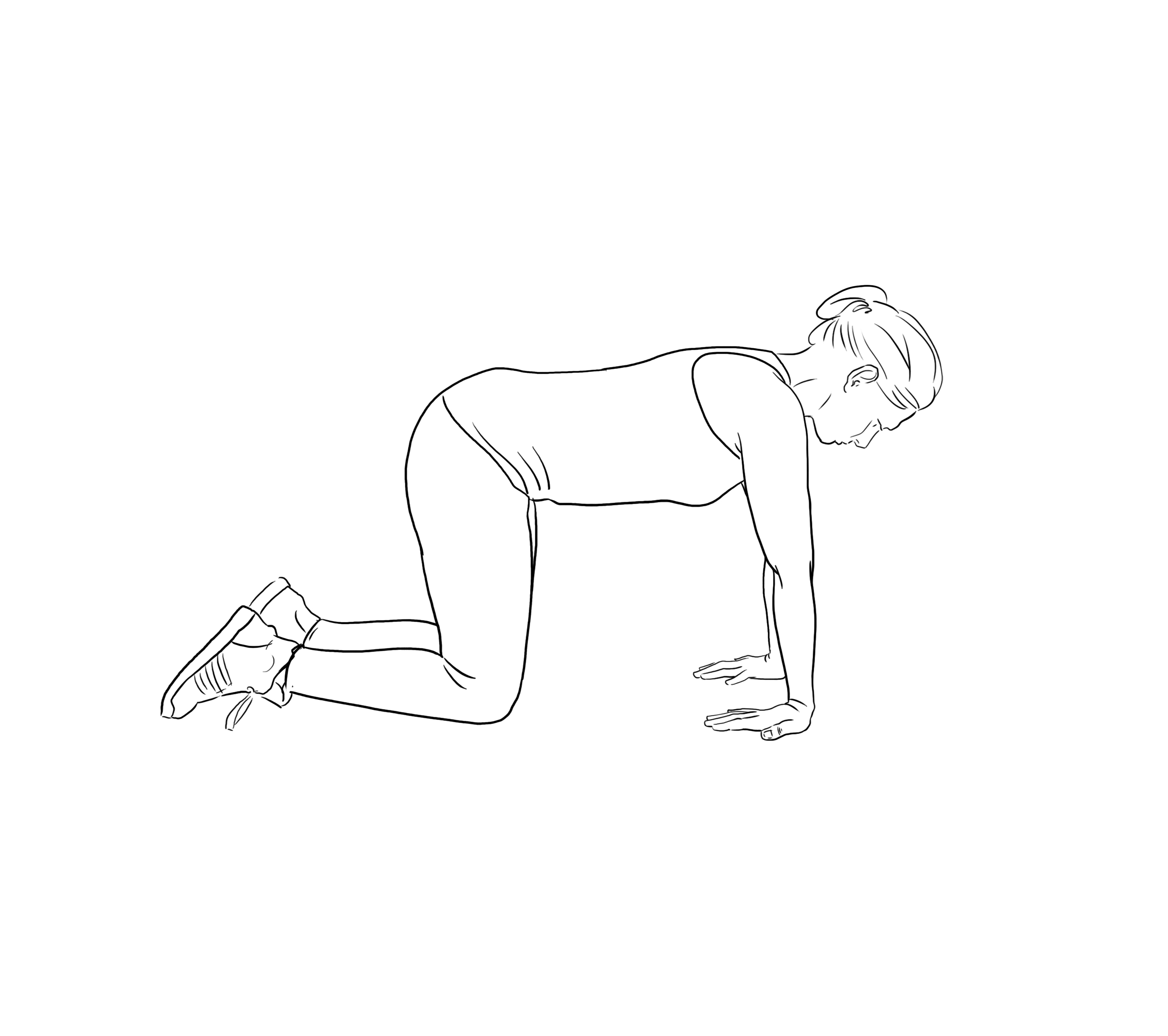

Kneeling forearm stretch

Opening the insides of the arms may help relieve compression and the constricted ROM through the elbow that may lead to tennis elbow. This posture also opens the backs of the wrists and carpal tunnel after gripping a racquet and also helps relieve the repetitive strain we can feel through the wrists after typing.

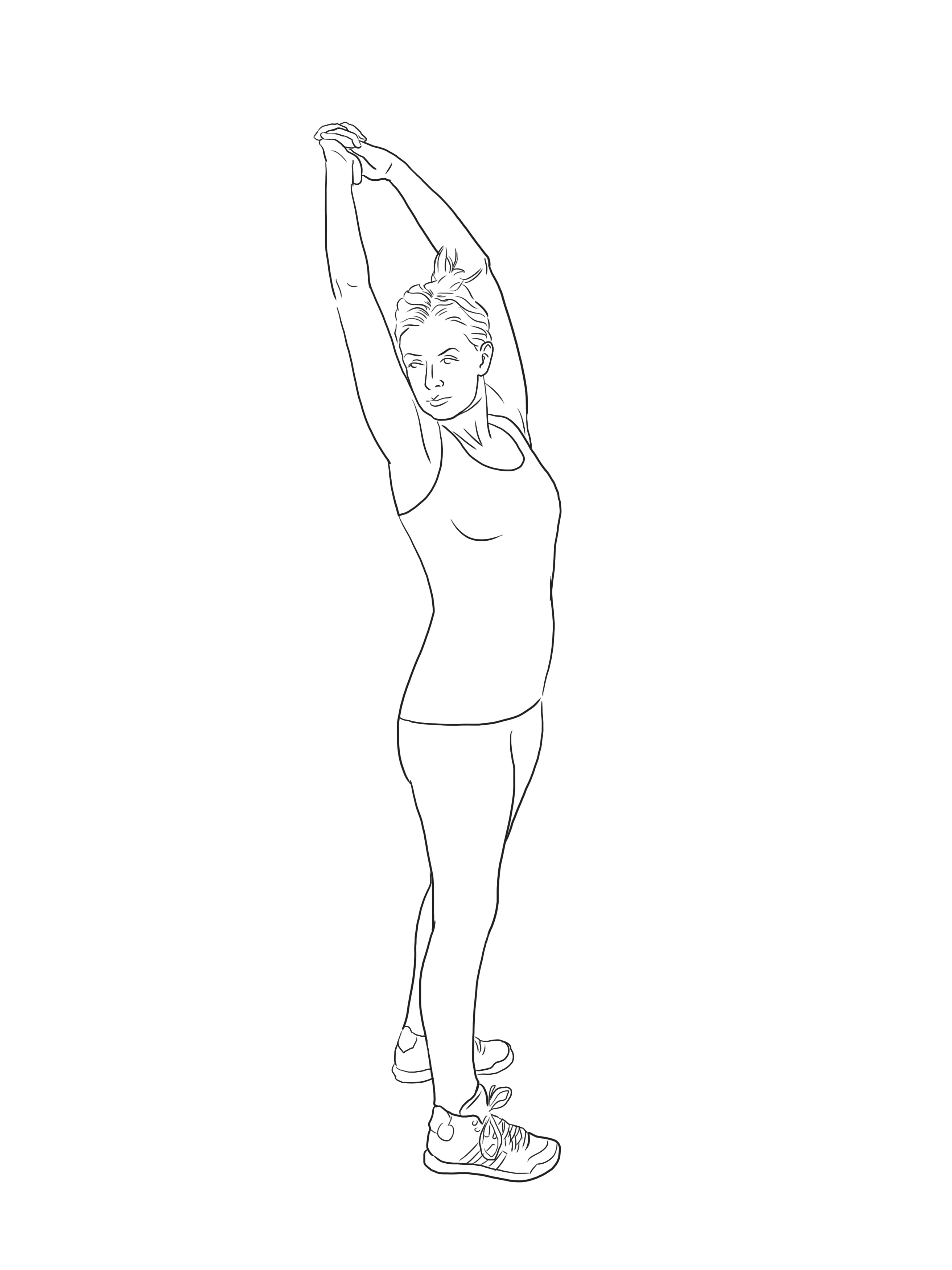

Triceps stretch

Opening the large latissimus dorsi muscle around the mid to sides of the back and up into the triceps on the underside of your upper arms helps restore ROM in muscles that have helped you move your racquet and may feel tense after a game. This may feel very different on both sides, but do stretch into both so your nervous system receives a sense of balance. This is also a great swimmer’s stretch.

Swimming

This gentle rotation that also lengthens the side lines of the body, follows the lines used in strokes like front crawl, but counters if you’ve been mostly doing the forward pulling in motion of breaststroke. A great front body opening stretch at any time too.

Standing reach-up back rotation stretch

Swimming leg movements work the outer hips strongly, so here you can sink down into lengthening this area to retain good ROM in all the hips’ natural directions.

Standing leg-under abductor stretch

The foot action of swimming where there is no solid ground to push against can cause tightening in the Achilles tendon, the strong strap running down the back of our ankles. This can limit motion further up into the lower leg and cause pain, even tendonitis when doing other movements and sports. This tendon is also foreshortened by wearing high heels, this stretch is useful for limiting damage from this fashion choice!

Sitting bent knee toe pull Achilles stretch

Find out more about Charlotte's yoga classes here.