Movement for Energy

Sep 25, 2022

How to Maintain Energy Levels

It is a basic truth that the modern world is highly stimulatory. For many of us, the amount we have to do, to watch, to read, to scroll about can be overwhelming, but even if we don’t find the barrage of information seemingly too much, we can become desensitised to how much this steals our energy.

With any action or reaction, we need time and space to rest and recover. This is mirrored in our breath, with the basic pattern of the energising inhalation followed by the releasing exhalation. Accessing states and movement where we are fully able to breathe out and have recovery and energy support within the practice, can also help us feel where can restore, rather than deplete energy resources.

Energy states governed by the nervous system

We have similar active and resting states within the nervous system. This is our complex system of nerves (from brain to outer body) that coordinates all body activity and sensory information by transmitting signals to and from all of the different parts.

Understanding the constant flux between tones of the nervous system can help us tune into our deeper needs. Within our autonomic nervous system, basic body functions such as heart rate, blood sugar levels and blood pressure simply get on with it behind the scenes, but we can have some influence through attention and conscious changes to our breath and mental responses.

Of its two branches, the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) puts us into more excitatory, active and energy creating states. It engages the stress responses and is referred to as ‘fight-or-flight’, with an immediate release of stress hormones adrenaline and cortisol, blood redirected from skin to muscles, brain, heart, increased heart rate and blood pressure, tense muscles and rapid breathing – all ready for us to take quick, decisive, full body action to protect our lives and those of others.

Many go into this state for exercise regimes, which can help us create strength, quick reactions, speed and a toned body, but if the only type of movement we do can wear tissues down, lead to injury and keep our muscles and fascia in tight, even painful and cramped states of holding tension. We are using up energy at a rate of knots here and sympathetic dominance or ‘constant alert’ may lead to burnout and fatigue, as well as related issues with issues, addictive tendencies, mood swings and intolerance.

This opposite tone is activated by the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) that takes us to a resting state. The PNS can be referred to in any combination of the following terms that describe its soothing and connective nature; rest, digest, detoxify, heal, recover and restore. All systems slow down and tensions that occur to keep up heightened responses – such as tense shoulders, jaw and fast breath – have the chance to release and soften. In long-term chronic stress or trauma, this letting-go, or even being able to feel we are tense can be difficult, and so we can be held in body patterns that use up energy when we are needing to restore.

This is also true of the immune system; inflammation is a protective part of the stress response and uses up energy at much higher rates than when we are at resting and healing states. Body safety and soothing is vital to bring this down as we receive signals that we are not likely to need the wound sealing and immune components that prevent infection from being wounded in fight, or in flight (Nutr Metab (Lond).2012;9:32).

Energy-draining inflammation is common in those with deeper fatigue – those with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome or ME can be ‘locked-in’ to sympathetic dominance (and anxiety states), which is using up their only available resources. So their inner world can be in highly energised hypervigilance and ‘racing mind’, whilst they may appear and feel physically drained. This mind-body fracture can be extremely difficult to live with, causing its own stress and exhaustion. We can’t keep up high activation states and can drop through to listlessness, demotivation and resistance to any movement; an enforced ‘recovery mode’.

Raising energy through mindful movement

The exercises in this article are to be practiced slowly and mindfully so there is movement that opens, releases tension, allows full release on the exhalation and helps you feel how to conserve energy and use it efficiently; but it can take a while to feel comfortable slowing down, being with more time and space and dropping away from goal-orientation. As with learning any new skill, the activity in the brain as we reroute neurons for familiarity can come with some heightened sympathetic response, but that can soon integrate and settle.

This type of practice with its roots in yoga and Qi Gong, has shown in many studies to allow the self-soothing mechanisms of the opposing and calming PNS (Health Psychol Rev. 2015;9(3):379-96). This is partly through breath and also the fostering of embodied awareness; a relationship with our inner world that helps bring presence and the safety to come down from high alert and danger signals.

It is not uncommon for people to live in ways that feel that they are ricocheting between high and low energy and mood states. Finding the ‘middle way’ (to borrow Buddhist terminology) is the route to finding sustainable and adaptable energy levels. If we recognise when our resources are depleted and need replenishing, we can adapt the movement we need at these times to be appropriate and supportive. In this way, we can find smooth transitions in movement that feed into adaptability and stress-coping in life.

Simple joint movements

Performing these simple motions before other exercise routines, after work or before bed can release tension held in joints that interferes with restoration processes and energy conservation. They can be done in various positions (eg lying down, sitting on a chair or cross-legged) to feel the different relationship with gravity. Slow down to feel the sensory experience without getting into the story of your body – why it might feel this way, labelling it ‘bad’ or bringing a label or diagnosis to the experience – and only move within your comfortable range of motion:

- Open and close hands to open out across all of the finger joints.

- Make fists and rotate into your wrist joints, one direction and then the other.

- Hold your arms comfortably out to the side palms up, then draw hands into towards your shoulders and back again, through elbow joints.

- With ankles still, wiggle and moves toes, opening them out as best you can and moving up to the top and bottom of your foot.

- Move your ankles in full circles, one way and then the other.

- Point and flex your toes, feet in same pattern as each other and then alternating for added focus; squeeze toes together as you point, spread them out as you flex.

- From lying with legs bent or sitting on a chair, draw one knee into the chest at a time and lift the foot up and down for movement through the knee joint, focussing on feeling the movement equal through insides and outsides of knees to support their natural range of movement.

- From lying with legs bent or sitting on a chair, lift each leg at a time and rotate the knee to move the head of the thigh bone deep into the hip socket.

- Move your jaw around and scrunch into your face to release tension and habits of expression there – note if pain has created holding a frown or clenched teeth and even exaggerate these to direct muscles to let go where they’ve been locked in contraction.

Energy-supporting sequence

Standing poses can provide a firm, physical rooting, grounding and earthing through the feet; creating energy that does not steal from the mind-body. In this sequence, we then come down to the earth through stages towards restorative, meditative positions; helping to transition from the more active to the more receptive. Focus on noticing when sensations or strength intensifies, breath in towards it – rather than constricting around it – and exhale fully to release and create softness wherever possible. For instance, we don’t need to clench the jaw to hold a strong pose and if we relax the shoulders, the arms can be held up from the belly rather than via tension in the shoulders, neck and chest.

Take your time between postures, standing with feet hip-width apart and with soft knees to begin and between postures – space to integrate the effects of movement, feel your inner state and breath coming to settle.

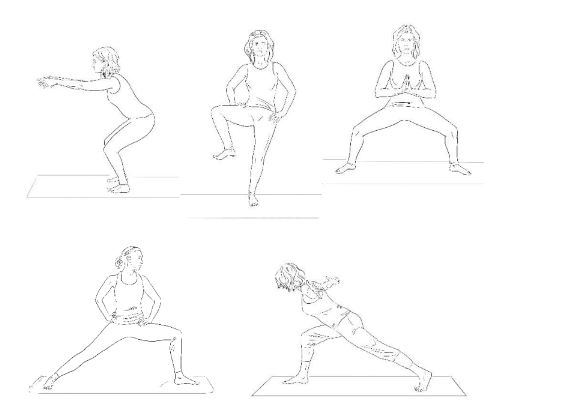

- Start standing, feet hip-width apart and parallel, with soft knees and letting the arms drop. On an exhalation, lift the arms forward to shoulder height and drop the bottom down to squat, retaining the same uplift through the spine. Inhale to lift back up to standing. Continue those, led by the rhythm of your breath.

- From the standing position, focus your eyes on one spot in front of you and then lift up one leg, bent at the knee, circling it at the hip, out and up from the centre. Keep lifting up the inner standing leg and spine, keeping the jaw and eyes soft. Repeat on the other side.

- Stand feet apart and turned out 90 degrees from one another in a wide horse stance. Bend the knees to a comfortable height. Inhale to lift the arms out and round to above your head as you bring the legs to straight and then exhale to bend again and bring your hands together at the heart. Continue this movement, letting the shoulders soften as you lift the arms.

- Turn one foot in about 45 degrees, the other parallel to its own thigh. Keep your hands on your hips to breath fully with strong work in the legs as you bend the front knee, only lifting the arms up if you can keep shoulders soft and breath long and full. Softly move to the other side.

- From hip-width apart, step one foot back into a high lunge, let the torso drop in line with the back leg, neck lengthened up from the shoulders. Open the arms out from the shoulders to open the chest and breathe fully before moving to the other side.

- Come back to the lunge first side and bring the opposite hand to front knee down to the ground (or blocks or a chair seat) to twist towards the front leg from the belly. Only lift the top arm if feels free in the shoulder or bring that hand down to the top hip. You can bring the back knee down if you need.

- After the other side of the last pose, come down via downwards-facing dog, with knees bent and heels lifted to open the chest and shoulders.

- Come down through (or an alternative to down dog) to knees bent, walking the hands forward so elbows come to the ground with hips above the knees. You can bring blocks under your head if you need, so you can find the position where you can fully drop in to resting the heart in this supported inversion.

- Ease yourself back into full rest in child pose or fully onto your front body if this doesn’t suit your knees or hips.

- Sit in a ‘z-legs’ position, twist away from the bent legs to twist and drop down onto your elbows or as low as feels natural, allowing your head to fully rest. Breathe into your belly to feel the twist unlocking tension there. Move to the other side gently.

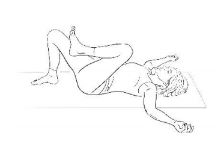

- Come to a fully resting position, with as lift as your legs need to feel fully open in your lower back. Spend at least 3 minutes there (10 if possible!) to truly allow the space created in movement to permeate into your fascia – feeling how deep rest restores energy reserves.

Discover Whole Health with Charlotte here, featuring access to yoga classes, meditations, natural health webinars and more...

Bibliography

Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers by Robert Sapolsky

The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel van der Kolk

Yoga, Fascia and Anatomy by Joanne Avison

Cranial Intelligence by Ged Sumner and Steven Haines