Increasing your self-soothing capacity

May 18, 2023

If you are feeling the heightened stress of expectations of achievement, constant decision-making and information overload, you are not alone. In this age of disjointed social groups and generations, building awareness and practices that help soothe our frazzled systems is more important than ever.

Self-soothing is the mechanism our bodies use to bring us back down to calm, after or even during the jolt of stress. This can mean the space to decide the most compassionate and helpful reaction in a crisis or feeling all systems back to rest after being revved up and reactive. When we’re in chronic stress and life has become one big hyper-vigilant ‘constant alert’, we can feel we’ve lost this route back to settling down and finding the peace we need for recovery.

Without healthy self-soothing abilities, living in continually heightened states can be exhausting, lead to whole host of stress-related symptoms (anxiety, insomnia, IBS and weight gain to name a few) and create fear-based and negative thinking that influence behaviours and decision making. This survival state can manifest as anxious states and reactivity, but also as more ‘frozen’ states of immobilisation, mental shut-down and disengagement from the world. Whichever protective mode we find ourselves in as a response to overwhelm, supporting self-soothing mechanisms can help our mind-bodies find states of safety and the way back to calm.

Good vagal tone

Our ability to come down from stress relies on action through the vagus nerve. It signals the calming parasympathetic nervous system (PNS), also known as the ‘rest, digest and heal’ tone, where we also dream, solidify memories and think from a more creative perspective. This is where we digest optimally, blood can flow fully to the skin and tense muscles can relax.

Vagus means ‘wandering’ (like vagrant or vagabond) and this is the 10th cranial nerve in the skull, running from the hypothalamus in the brain and the only cranial nerve to move into the body, running down to the chest, diaphragm and all our visceral organs via the solar plexus, essentially wrapping around our heart and core areas. The vagus nerve activates ‘reset’ after a stressor has passed – “putting on the brakes” to come back to a reflective place after the impulsive reactions of stress.

When this ability or ‘vagal tone’ is good, we can access this self-soothing mechanism with ease, but poor vagal response can mean we struggle to come out of anxiety.

Simple techniques for activating your vagus nerve can provide quick relief from nervous system hyper-drive:

- Being around people who offer the safety and connection of relation of positive emotions and joy.

- Conscious breathing with a focus on the exhalation, breathing in deeply to let the calming out-breath really flow, even making an ‘ah’ sound to open the back of your mouth and release tightness around the temples and jaw. Slow breath has also shown to encourage good vagal tone (Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2013, Article ID 743504).

- We can access the vagus nerve directly behind eye balls, in the palate of the mouth, the tongue, the ear canal and lobe and surface of the lips. Yoga teachers often talk of ‘softening the eyes, face and jaw’ for this reason and we often soothe ourselves automatically by touching our lips, opening our mouths and rubbing our ears.

- Touching or stroking your body (including face and lips) with kindness and self-compassion; placing a hand on your heart, belly or anywhere that feels calming plugs into our mammalian need for warmth and touch.

- Massaging the forehead is also soothing as activates the trigeminal nerve there, that then provokes the vagus nerve’s soothing effect.

- Ask for a hug or give one to yourself and breathe deeply to offer ‘letting go’ to your whole body. After 20 seconds of a hug, we produce the hormone oxytocin, the ‘love molecule’ released by breastfeeding mothers, parents bonding with their children and those in love.

- Washing your hands with warm water or submersion in warm water.

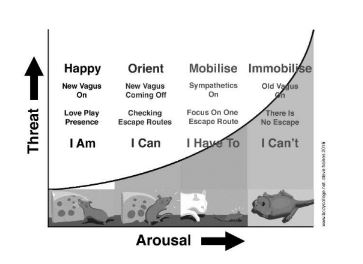

Polyvagal theory

A relatively recent change in thought on stress responses was first presented as Polyvagal Theory by Dr Steven Porges in 1994 (Cleve Clin J Med. 2009;76(Suppl.2):S86–S90). This moves on from viewing our autonomic nervous system reactions as either sympathetic (fight-or-flight) or parasympathetic, but proposes “a hierarchical system” of three circuits. Within this system, the more we are challenged, the more likely we are to drop from more conscious responses that involve the ‘evolved’ or mammalian front brain, towards more primal, older circuits driven from the ‘reptilian’ lower brain, in an attempt to survive.

This happens in the following way as shown in the illustration:

- The new vagus - we start out trying to use our “social engagement system” to look at each other and resolve things warmly; that’s our first vagus parasympathetic circuit and allows us to be fully present in the moment. From there, we can observe and evaluate possible danger or threat with a sense of space and action appropriate to the situation, seeing different options and having foresight of their consequences.

- Fight-or-flight response (sympathetics) - if that fails, we devolve into a primitive survival response, where adrenalin and vigilance take over, with impulsive, instinctive and emotionally reactive decision-making, often from a fear-based stance. If we were startled and just check out that noise and find it doesn’t pose a threat, from here we may drop back into the new vagus state, especially if we have practices of being aware and present such as meditation, yoga and t’ai chi behind us.

- The old vagus – if the first two options fail us, we have chronic stress or trauma, or feel overwhelmed by the choice of how to react, our ancient reptilian vagus circuit takes over and causes immobilisation, aka freeze or dissociation. When we’re caught in old vagus mode, we can end up following ‘old strategies’ that made sense in a previous context eg comfort eating, feeling a lack of body awareness, fear of change and lack of adaptability and attachment to regimens, routines, habits or preferences that may no longer suit our needs.

Grounding

The way out of reacting in these limiting behaviour options of fight, flight or freeze is firstly to orient to our present surroundings, where we consciously notice where we are in time and space. If the present situation is actually safe and our reactions are either a result of habitual stress or trauma (living as though the event or unsafe environment were happening now), we then have the opportunity to look around and listen fully to start to register safety.

If possible, being in relation with others at that time helps bring us back to the new vagus; eye contact, smiling and touch from people we trust can bring us back from dissociation and back to the grounding of feeling we are in our bodies.

Mindful movement and vagal tone

Mindful practices such as yoga, t’ai chi, Qi Gong and any activity performed with consciousness of moment-to-moment feeling (without the judgment of ‘like or dislike’), encourage us to develop good tone in the new vagus (Sage Journals. 2016;17(1):5-15). The interpersonal attunement felt in classes that promote this, encourage heartfelt connection with other humans and ultimately greater new vagus states of social connectivity and engagement.

Such practices, as well as meditation have shown to increase levels of the neurotransmitter GABA (gamma-amino butyric acid) whose release is signalled by the vagus to soothe the brain, still the mind and decrease anxiety (Curr Behav Neurosci Rep. 2016;3(4):328–339).

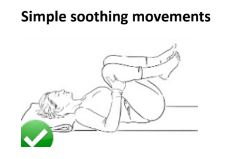

Simple soothing movements

Coming to the ground promotes mind-body safety as we are fully held and supported. As more space and presence is offered, we can feel vulnerability too though; no bad thing, we need to be able to feel to fully engage with life, but also need to practice self-compassion and full exhalations to meet the experience with calm.

- Drawing knees into the chest in any foetal position protects the front body and creates the soothing sensations of nurture. They also relieve tension in the lower back that can result from the tightening of tissues in chronic stress or trauma.

- You can stay here in stillness as a meditative position or move in any way that feels natural to create the soothing effects of self-massage that reduce stress hormones and raise levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin for social engagement (J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(4):346-51).

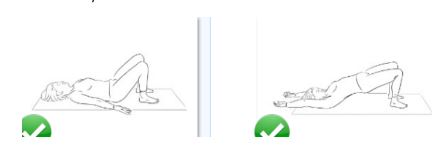

A bridge pose promotes safety as we work the legs strongly and also undulate the spine up and down with the breath to loosen the diaphragm and promote ease of breath.

- From lying, feet hip-width or wider, feel good contact with the base of the big toe, so that as you inhale and bring the arms up and over the shoulders, you direct the lift into the chest rather than the lower back. Open the arms as wide as the shoulders feel comfortable.

- On the exhale, lower the spine back down, vertebra by vertebra, hands coming to meet the ground in synch with the tailbone.

- Lift up and down as long as your breath can stay long, face and jaw soft, eventually holding the pose up for as long as you feel neither stress nor strain in the body or breath.

- Come back to the foetal position slowly to relieve the lower back.

Standing soothing movements

Standing is soothing as promotes the strong legs we need to move away from danger. These movements from the Qi Gong system help us to move ‘from the belly’, our seat of intuition that supports us listening and responding to gut feelings rather than hypervigilant voices of a stressed mind.

- In stillness, hold hands in front of your belly, fingers slightly apart, completing the circle of the pelvis at the hara. In this meditative space, we connect with the belly, and a deeper intuition of ‘what is here right now’. You can come back to this reflection after each movement.

- Allow the arms to swing around the midline of the body; hands like weights at the ends of arms as ropes. Twist through the tissues of the torso, knees lightly soft.

- Hold an imaginary football just higher than eye height. As your neck feels comfortable, keeping your focus on the ball, rotate it fully in front of your body, bending your knees as you reach it right down past your inner legs. Then rotate in the opposite direction.

- Rotate one leg at a time in the hip to loosen this area where we can hold much tension, with leg bent and hands on hips or held upwards. Keep the eyes softly focused on one spot to create balance that helps foster the steady attention that ultimately soothes the mind.

Supported inversions

These variations on Viparita Karani (waterfall practice) from yoga raise the legs above the heart and head to allow full rest in the nervous system. Gravity simply allows blood flow down from the lower body. There is a soothing effect in the front brain as the back of the skull able to open; this area is where the vagus bundle sits and can tend to become compressed with modern postural habits of hunching and then having to lift the chin to see forward, often to a screen. The supported chest opening allows full breath into the front ribs and slow breathing to evolve without force.

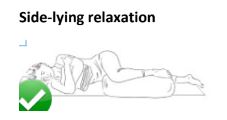

Side-lying relaxation

This variation of the final relaxation in yoga, savasana (corpse pose) offers the same meditative space to assimilate experience and the movement before, but lying on the side can be more foetal and soothing. You need a high enough head support to accommodate the width of shoulders, a bolster or cushions under the top leg to keep the hips open and a rolled blanket or cushion to hug and retain space across the chest. Cover with blankets to feel cocooned and stay present with the breath, following the inhalation up the spine and the soothing exhalation down.

Discover Whole Health with Charlotte here, featuring access to yoga classes, meditations, natural health webinars, supplement discounts and more...