Exercise for Cognitive Function

Jun 07, 2022

We know intuitively that when we move around, we feel clearer, sharper. When we don't move around enough, then we can feel more mentally sluggish, memory can become little harder to access, and reactions slower.

We can divide cognitive process into six types – attention, perception, memory, language, learning, and higher reasoning. These can both can occur simultaneously and independently, they rely upon each other and intertwine for that orchestration of how we think, feel and move our way through life. Learning new skills and new ways of thinking are supported when we also learn new movement patterns eg a new dance, type of movement to increase our cognitive fitness and longevity of our mental processes.

When we get moving, we increase circulation, we exercise the blood vessels themselves and this helps to prevent neurodegenerative conditions known to create cognitive impairment (Journal of Internal Medicine, 2011; 269(1): 107-117). Exercise also helps to control blood sugar levels (J Physiol, 2003; 546: 299–305); recent studies have shown that those whose glucose tolerance and blood sugar balance is impaired tend to have a smaller hippocampus where the seat of memory in the brain is actually shrunk in terms of actual volume as well as function (Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2003; 100(4): 2019–2022). So, parts of the brain that tend to be worked more tend to grow often larger and more robust. As exercise increases the flow of oxygen-rich blood to the brain, it directly increases circulation there and the health of the blood-brain barrier, how we deliver nutrients to the brain.

In this way, aerobic exercise – running, swimming, cycling – is the most beneficial for basic brain health because as it increases our heart rate, more blood and oxygen are pumped to this most important organ of survival (Neuroscience 2012; 202, 252-266). Exercise is mimicking the ‘fight-or-flight’ response so increased mental acuity is part of the picture to sharpen our abilities to respond, focus on where our body goes and take cues from the environment and people around us. This is one of the reasons that group activities are so helpful for mental function.

We need a range of activities to switch mental function as mind-body connection from one type of task to another. So, adding to aerobic exercise that which has a problem-solving element about it like housework, gardening, building, DIY, all help to cultvate our full range of cognitive function. When our actions have a purpose, they can make more sense to our mind and we just get on with them.

Maybe most importantly of all, the more often we can get out into nature the more we are able to also be responding to the natural world around us, where we are continually responsive to the changing ground underneath our feet and allow stress hormones to come down. Missing out this key part of our optimal function makes reducing the psycho-social stress of modern living very difficult and this continual brain overwhelm can wear down cognition.

Nature helps bring us into the present moment and it is this open-mindedness that we replicate within mindful practices. When we practice any movement or exercise with full consciousness of the experience, we are bringing key aspects of cognitive health online. Yoga is such a mindful practice and has shown to have particular benefit for brain function, as well as t’ai chi and qi gong.

In one study, 108 adults between 55 and 79 years of age were divided into two groups; 61 of these attended hatha yoga classes and the others met for the same number and length of sessions. They simply carried out stretching and toning exercises, rather than the focussed attention also part of a yoga practice. At the end of the eight-week study, the yoga group performed tests of memory recall more accurately and faster than before, with increased “working memory capacity, which involves continually updating and manipulating information”; their ability to mentally change and adapt as they switched tasks was increased. The non-yoga group showed no significant change in cognitive performance over time (The Journals of Gerontology, 2014; A(9):1109–1116).

Differences in outcome were not related to those of age, gender, social status or other demographic factors. Rather, the mindful attention of this specific form of exercise was attributed to the positive change. “Hatha (physical) yoga requires focused effort in moving through the poses, controlling the body and breathing at a steady rate,” one of the study researchers commented. “It is possible that this focus on one's body, mind and breath during yoga practice may have generalized to situations outside of the yoga classes, resulting in an improved ability to sustain attention”.

This correlates with evidence where the brains of elderly female yoga practitioners were imaged and found to have greater cortical thickness in the left prefrontal cortex, the area in the frontal lobe associated with cognitive function such as memory and attention. One of the researchers in this study said; ““Like any contemplative practice, yoga has a cognitive component in which attention and concentration are important.” (Front. Aging Neurosci., 2017; https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2017.00201)

Cross-lateral movement and balancing

As the two sides of the brain are responsible for controlling opposite sides of the body, any quadrupedal movement where our natural movement is opposite leg to arm at any given time, is a cross-lateral movement ie one that encourages communication between the two hemispheres of the brain. Research looking at quadrupedal movement in adults concludes that "Performance of a novel, progressive, and challenging task, requiring the coordination of all 4 limbs, has a beneficial impact on cognitive flexibility..." (Hum Mov Sci. 2016 Jun;47:70-80).

So if switching movement types and direction forwards, backwards and side-to-side, the brain processing of these challenging signals supports memory, concentration and productivity. If we add in balance too, focus is increased as we need to stay aware of where our body is in space as it continually rights itself back towards the centre of gravity. Regular balancing practices have shown to improve memory and spatial cognition, a sense of where and when we are at any given moment (Sci Rep. 2017; 7: 5661). This ‘presence’ is only allowed fully when we keep our attention with the steady, fixed gaze and easeful breathing that is the sustained attention described in the aforementioned study.

This is one of the reasons that yoga reduces stress hormones; we cannot tensely hold ourselves in such positions to stay there for any length of time. It is only possible if we learn to find ease within a strong and challenging position. In this way, we become more adaptable in both body and mind as our body ceases to register the practice as a ‘stressful event’. Reducing the sympathetic nervous system action of the fight-or-flight response stops us being more reactionary in the face of change, and instead increases neuroplasticity; our ability to adapt and stay flexible with change. This is a great recipe for maintaining and growing cognitive function.

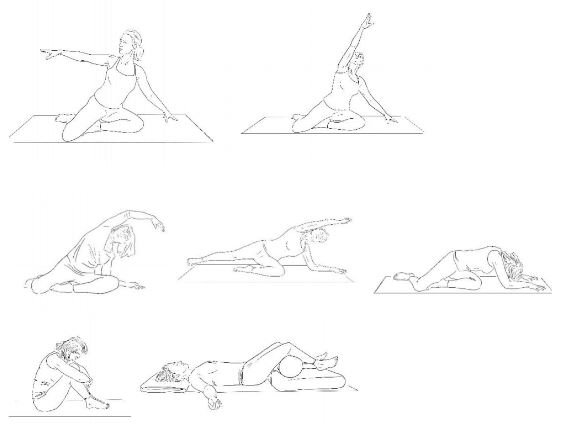

The following two sequences help cognitive function in slightly different ways and can be practiced alone or as one longer session.

Standing plane for balance

- Standing feet hip-width apart and knees soft, release the shoulders and jaw before bringing your arms into a circle. Then gazing at the spot between your hands, retain this focus and then take your arms into full circles, following this trajectory with your eyes. Stay aware of your feet on the ground, bending your knees when reaching down. Change the direction and notice any differences in focus there.

- Hands on hips, focus on one point directly in front of you and then lift one leg to circle the knee and hip forward and out. You can either touch the toes to the ground between circles or keep the foot up for more balance. Breathe fully to hold balance without tensing your shoulders or temples. Repeat on the other side.

- Step wide with feet turned out at about 45 degrees in a ‘goddess’ pose. From hands together at your heart, inhale your arms out wide and above your head as your legs come to straight. Exhale back down to your heart, bending your legs, knees pointing towards your toes and drawing up from the belly.

- From the last stance, revolve your feet so one is turned in, the other out 90 degrees – front knee bent and arms out into a warrior pose. There, inhale the arms up above your head as you bring legs to straight and exhale back down to arms out, front knee bent. Follow as many of these motions as your breath can stay long and spacious and then hold the pose.

- Revolve the back heel and hip in to come to a high lunge, feet hip-width apart. Lean the torso forward for a ‘humble’ version, arms out to the side at shoulder height.

- Step the back foot in to transfer the weight to the front foot and open out the top hip to lift the back foot into ‘half-moon’ balance. Look at one spot down for focus and lift the top arm to open the top shoulder and rotate open the chest. Breathe fully before stepping back through the lunge, to warrior to goddess and then turning to the other side, steps 4-6.

- Come to a standing meditation to integrate the movement back to the centre.

Seated plane for grounding focus

With the ‘z-sit’ positions here - where one thigh bone is rotated in and the other out - the hips are moved in a way that is beneficial and accessible for most. Tightness around the hips, belly and lower back can interrupt blood flow up from the legs back to the brain, so an important consideration for oxygenation for cognition. This is also a great alternative to sitting on chairs at home or whenever you can, as sedentary behaviours and the slump of chair-sitting can greatly compromise circulation.

- In ‘z-sit’ with right leg turned in, left turned out, support yourself with right hand on the ground. Reach the left arm out to the side and spend some time focussing your gaze there. Feel uplift through the spine with the inhalation, softening in the shoulders with the exhale.

- From there, rotate the arm in full circles – down past the front of the knees and reaching up and over. Allow the movement to come from the hips and belly so you are involving the side body, chest, shoulders and neck in their most natural organisation. Keep your focus completely on where your hand is in time and space as a ‘moving meditation’, so your brain has to constantly adjust to its changing position.

- Then dropping onto the right forearm to come lower, reach the left arm over the left ear to settle into a side flank opener that raises the heartbeat a little. Find a position with the head where you feel long in both sides of the neck to be able to stay and fully breathe with comfort. Repeat these first three steps on the other side.

- Lengthen out the left leg off the floor with the foot flexed (opposite to pointed) and little toe side of the foot parallel to the ground so that the thigh revolves slightly in. If your shoulder has the space, lengthen the left arm out away from the left foot. Breathe fully into the exhalation as this becomes more active.

- Bring the left leg back down and rest into a twist to the right, elbows to the ground where it feels they are equally weighted. Let the head drop there to release the neck and then move to steps 3-5 on the other side.

- Come to centre to rest into a seated foetal position, letting your focus come back to the midline.

- Lying down in savasana (corpse pose) to allow your mind-body to fully integrate the movements and attention before. Raising your legs even slightly here (on bolsters as shown or even to a chair seat or sofa) creates rest in the heart and increased circulation to the brain.

Charlotte's Whole Health platform offers a range of classes, supportive materials, natural health webinars, meditations, health supplement discounts and much more. Click here for further info.