Easing Lower Back Pain

Apr 21, 2022

With experts estimating that 80% of people will experience lower back pain at some time in their lives (Neurol Clin. 2007;25(2):353-71), this is an issue that is only getting worse as we spend more time sitting on chairs. It is no surprise that moving is an effective antidote for this debilitating issue (Spine. 2008;8(1)213-225), but the pain involved can create a Catch-22 cycle. The holding and fear of exacerbating the issue can leave people avoiding exercise, becoming confused about their capabilities, and what can help, and what can worsen their symptoms.

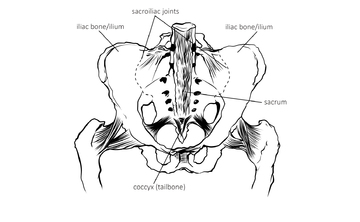

The sacroiliac (SI) joint

Understanding some lower back anatomy can help us make sense of why this area may become a source of tightness, pain or inflammation. Many issues arise at the SI joints, the two sites where the lowest bone in the spine – the sacrum – sits into the bowl-like bone of the pelvis (fig.1). These joints are calibrated to the very individually human bipedal way of standing, so the sacrum acts like a keystone supporting the spine above and distributing the weight of the upper body down through the legs. We move from and around this area and the SI joints can become loosened eg in pregnancy or fused with age or sedentary habits. If the pelvis is tipped to one side, for the spine to compensate and lift vertically, one joint will become more open and the other more closed. Either effect on a joint can lead to pain.

Psoas support and release

Running closely in front of the SI joints is the psoas muscle that allows us to stand upright on two legs, is located deep within the front hip joint and lower spine. Among its many functions, it is part of our central body support, stabilises the lumbar spine (lower back), keeps the SI joints from being too loose (a common source of lower back pain) and is used in hip rotation and walking. It is also a key part of our breathing apparatus as it connects to the diaphragm; both tense in response to stress.

When the psoas actions of bending over and lengthening the lower back are in balance, our lower back can sit in happy neutrality, curved inwards with the pelvis tilted 30 degrees forward - where the psoas naturally elongates and falls back towards the spine.

In fig.2 we can see that there is a chicken-and-egg relationship between losing support from abdominal muscles at the front of the body and pull into the lower back. The right-hand figure has a tightened psoas with little give in compensation, and often a result of stress or trauma. This creates compression in the lower back and difficulty standing up from the front of the spine; a vicious cycle.

To begin unravelling such patterns, simple doing lots of ‘core work’ to ‘flatten the abs’ is not the answer. This may draw in the belly, but leaves the psoas tight, this muscle usually needs release not more work, which can be started with:

- 3 coming to a neutral psoas position, lying on the ground in Constructive Rest Position for up to 15 minutes and breathing into belly and diaphragm

- 4 from there, placing a tightly rolled small towel across the shoulder blades (not into the lower back) opens the front body and chest, which can relieve compression in the lower back by helping it lengthen. This is great lying down, where we don’t have to hold ourselves up from gravity.

- 5 then coming to counter this front body opening, draw the knees into the chest, tucking your hands into your ‘knee pits’ so your knees can open as comfortable. This is a gentle lengthening for the lower back, where you can roll around and play with any movement that feels good there.

Stability between your ribcage and pelvis

There are of course so many variations of how we stand and there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Paying attention to our own patterns and any shifts we have away from our design can help find the posture that our lower back needs.

Looking at fig.6 we can see that in the left-hand example (A), the person’s ribcage is easily above their pelvis, with these ‘bowls’ facing each other. This is where we rise up most effortlessly through the S-shaped curve of the spine and the lower back sits comfortably. The other examples are how this relationship can commonly go off course. In figs. B, C, D you can see the pelvis moving further forward of the mid-line and the head also moves forward to compensate for the weight and centre of gravity change.

Each of these affects the natural curve of the lower back, that optimal 30 degrees (A) where the psoas is not stressed and in B is exaggerated and compressed (a banana back or hyperlordosis). This is a need for psoas release, alongside support at the abdominals.

In C and D it is flattened, which can also occur from ‘tucking the tailbone under’ when standing - not a helpful physical instruction for the posture over time. Allowing the tops of the thighs to move back to help re-establish the curve in the movements that follow. This situation can also come from over-gripping the stomach, from collapse in the chest or too much core work, or both.

Abdominal awareness

Standing with your knees bent, feet hip-width apart, you can move between really tucking your tailbone under (where you lose lift up through the inner legs) and really sticking it out (where you lose lift up through the belly). Investigate where you find your natural curve in between; sitting bones moving forward, without drawing the tailbone under and belly drawing in and up.

You can then investigate the curve of your lower back with your belly in this exercise where you feel your breath in your ‘abdominal box’. This is the area you enclose when you place your fourth (ring) fingers on the top of each hip bone (bony protuberance to each side of the groin), each thumb on the bottom rib (fig.7). As you breathe, feel this area becoming smaller at all four points with the exhalation, larger with the inhalation. Here, you are feeling the point that stabilises the rib cage and the pelvis and where the lower back is supported at the point of the navel, particularly with the exhalation. Honing awareness here can help you breath into this area that can be held in tension from pain or self-protection.

You can then feel this area as you open the front body (and psoas) in a lunge. This position can feel ‘pinchy’ in the lower back for many, but if done intelligently, can inform and strengthen the support you need from the belly there.

- In the first figure, bringing one foot forward to a right angle with the knee, bring the front of one hand to your belly to encourage (not force) uplift here and the back of other to your lower back to coax (not drag) moving down here.

- In the second figure, from there, you can interlink the hands behind you head to open out the elbows and lift the chest. This helps you lift the spine from the base of the skull and you can meet that space drawing the belly in and up, feeling the same action that the hands directed before.

Fascial release

We need to keep moving generally, and specifically around the mid-torso for lower back health (eg with walking), to retain what is referred to as ‘slide-and-glide’ in our fascia. This is the web of connective tissue that runs throughout our whole body, joining every part of us and here, through the lower spine, SI joint and via digestive and pelvic organs at the centre, out to the periphery of our bodies.

As we age, fascia can become less mobile and drier and more prone to ‘stick’ or form lesions or adhesions that lead to pain through restriction and inflammation as it cannot ‘give’ as we move. Add in physical trauma from accidents, abuse, surgeries, infection or radiation that can create fascial distortions and this whole mid-section of the body can commonly become more rigid and less adaptive within normal range of motion.

Tightness in one area of the body ripples out into others and the site of pain very often transferred from its point of origin, so a lesion in the digestive or reproductive organs can easily transmit out to the SI joints (where the right and left sides of the colon attach), other areas in the lower back and reaching out to hips, upper back or shoulders. Lower back pain, pelvic issues and digestive disorders go hand-in-hand-in hand – especially when the sacrum is out of place due to unevenness in the pelvis, which can be a result of habits such as repeatedly crossing your legs in one direction.

The medical route for adhesions can be adhesiolysis, surgery to cut them out, but of course this can cause its own trauma, more scar tissue and lesions tend to grow back in 70% of cases. Abdominal massage and sensitive movement in this area can help restore the hydration and slide-and-glide needed for function and even possibly scar tissue flexibility that can lessen pull on the lower back.

Exercises that create small, rhythmical and pulsing movements through the body help all fascial slide-and-glide and those that move through the belly support lower back ease. You can do these lying down moving knees to twist side-to-side, on all-fours rotating the pelvis or standing, to engage the feet; extremely important for lower back health. Foot arches that have dropped can leave a person more prone to lower back and neck issues as they lose their natural uplift through diaphragms at the insteps and pelvic floor below and less able to contain their belly at the front.

- 10 hold an imaginary football in front of your chest

- 11 inhale to reach one hand back behind you, following it with your gaze to turn from the belly. Exhale to bring it back to join the other hand, then inhaling that back. Move from side-to-side, feeling the movement originating in the belly, reaching as far back as your lower back is comfortable.

- 12 bend your knees and allow your spine to hang down and decompress, fully dropping the weight of your head. You can roll up and down a few times from here, allowing your body to organise itself to standing.

Hip and sacrum release

Another way to feel movement into the fascia around the sacrum also involves opening the front body and the hips, where movement is vital for lower back health. Both of these factors are hindered by sitting hunched and dropping backwards into our lower spine, a contributing factor in most back issues (Indian J Occup Environ Med. 2016;20(3):125-128).

- 13 coming to a ‘cobra pose’ on your front, open your feet as wide as your lower back needs to feel comfortable. Place elbows under your shoulders or further forward if you feel compression in the lower back; find the place your spine feels long and uninterrupted, which is where you will also strengthen muscles either side of the spine.

- 14 from there, bend up your right knee to where your hips still some kind of even. Rest and breathe here to feel opening in the left psoas and softening in the lower back; keep lifting up through the front spine, shoulders dropping away from the ears. Then begin to explore small movements taking the right knee further away and closer into the body, creating little movements in the hips. Feel how the tissues into the lower back move and respond. Come back to centre (resting your head down if you need) and then move to the other side.

- 15 counter this with back body opening in a seated foetal position or a child pose for long enough to feel release in your lower back.

To access Charlotte's Whole Health with access to current and past webinars on back pain and much more, click here.