Does yoga help reduce inflammaging?

Jan 19, 2023

From environmental pathogens to modern diet, our cells are inflammaging – aging through increased inflammation. How can yoga help?

By Leonie Taylor and Charlotte Watts, co-authors of Yoga & Somatics for Immune & Respiratory Health

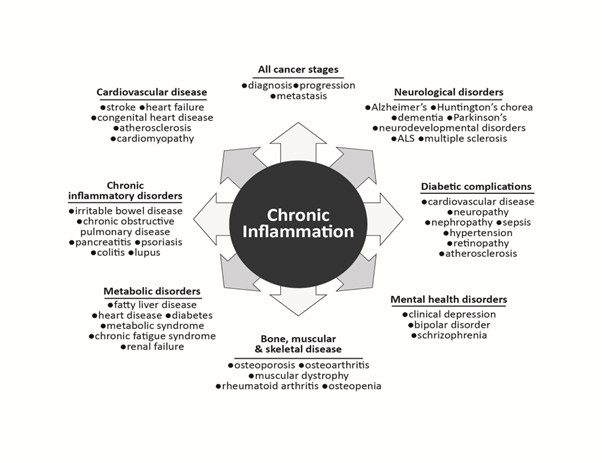

‘Inflammaging’, a term coined by Italian researcher Claudio Franceschi in 2000, refers to the low-grade chronic inflammation that often characterises the ageing process. This may partially explain why some older people suffer more from diseases such as COVID-19. Beyond this pandemic, many refer to the creeping symptoms related to inflammation – such as joint pain, loss of mobility or issues related to immune and respiratory health – as an inevitable sign of ageing.

‘Ageing is often described as the progressive accumulation of deleterious changes over time leading to a loss of physiological aptitude and fertility, an increased susceptibility to disease, and ultimately to death’[1]

While ageing is a process of degeneration, having an awareness of where we can engage in our capacity to self regenerate also stems from where our body systems meet the stresses placed on them. Geroscience, the science of ageing, considers the intertwining processes of disease. Four of the seven recognised factors of ageing also tie into processes of disease that tip the balance of regeneration to degeneration (the natural cycle of life and death):

- Decreased adaptation to stress causing anxiety, overwhelm, sensory overload or other ‘stress-related symptoms’ such as fatigue, insomnia, irritability, depression, inflammatory conditions and weight gain – through increased appetite and the stress hormone cortisol that raises insulin and switches on fat storage[2].

- Epigenetic dysregulation, where behaviours and environment change the way our genes express themselves[3]. Epigenetics is a broader way of viewing how our gene expression is influenced by factors over our lifespan (and from that down the generations): stress, trauma, disease, lifestyle, exercise, diet, etc. Pathogens – from smoking to germs – can weaken our immune system.

‘Increasing evidence shows that epigenetic deregulation is a common mechanism in cancer.’ [4] - Macromolecular damage[5] macromolecules are large molecules, most commonly proteins, nucleic acids and carbohydrates. Neurodegenerative diseases, which have been linked to the oxidisation and aggregation of proteins, increase with age. Data shows that macromolecular damage may be causative in ageing as effected proteins can change the ‘signalling in cells/tissues, which can alter cellular functions and appear to play a role in a variety of age-related diseases – e.g., cardiovascular disease, cancer, Parkinson’s disease, and diabetes’[6]. This damage is from oxidative stress, which is an imbalance between free radicals (unstable, damaging molecules, for example in sunlight, fried foods, certain pesticides and cleaners, radiation, pollution, cigarette smoke) and antioxidants (immune-supporting compounds in food, vitamins A, C and E, minerals zinc and selenium) in your body[7].

- Derangement of metabolism[8] Before the onset of farming, humans ate predominantly complex carbohydrate (plant) foods that slowly release sugars. The refined sugars of modern diets upset our natural blood sugar balance, causing glucose highs and lows, rather than the sustained, constant energy feed that our body cells require. This can set off inflammatory responses, and sugar directly causes inflammation, especially when eaten with fats, for example in pastries and cakes.

With stress and inflammation clearly involved, we can see a route to engaging with our own health and quality of life, essentially having some agency with our own epigenetics – how we move, breathe and relate to our own inner narratives and relationships with others. Adding in awareness of our responses to stressors – and how mindful attention, practices and compassion can transform these – and ripple effects through the other factors can be observed.

In The Myth of Normal[9], Dr Gabor Maté talks of: ‘The wear and tear on the body of having to maintain its internal equilibrium in the face of changing and challenging circumstances, trauma salient among them.’ He cites a Yale study in which cumulative stress is seen to increase biological ageing.

Studies into the role of microbiotics in mood and cognitive function in elders[10] have shown that mind-body disciplines such as yoga and tai chi help to reduce cognitive decline and mood disorders, helping to modulate nervous system function, metabolism and immunity. Various research studies over the years have backed up these assertions that yoga and meditation can dramatically reduce the effects of stress, increase conscious self-regulation of the nervous system and therefore slow down harmful degenerative affects.

So what practises can help us to prevent the ravages of time and regenerate rather than deteriorate?

- Breathing for regulation

Most humans breathe inadequately, allowing them to survive but not to thrive. Stress can cause us to breathe in before the exhale has completed. Bringing attention to full, fluid, coherent, whole-lung breaths otimises gaseous exchange, lowers heart rate and regulates our autonomic system. Resting into the still point of the bahya kumbhaka (pause at the end of exhalation) can allow us to complete the recovery of the out breath before the action of the inhale. In Yoga & Somatics for Immune & Respiratory Health, we explore various gentle and accessible pranayama – breathing – practises that can be incorporated into your everyday to relieve stress and inflammation.

- Spiralling, undulating and twisting

Synchronising spinal undulations with the natural continuum of the breath brings the autonomic nervous system into a coherent space. Mindful breathing with motion helps us to physically feel where our boundaries are. The fluidity of twisting, undulating and spiralling, focussing on space and breath, allow us to connect the entire story of breath and body around the spine, through the viscera. Movement that follows the innate curves and spirals of the body increases hydration and mobility within and around the tissue and organs, releasing tension, fascial fatigue and the sense of ‘stickiness’.

Benefits for the immune system include:

- Unravelling patterns of stress, trauma and habitual movement.

- Supporting healthy digestion by relieving stagnation around the belly and diaphragm.

- Increasing fascial ‘slide and glide’ which relieves inflammation and encourages adaptation.

- Adrenal response exercise

This helps us to reset the head, neck and shoulder responses to nervous system input, alongside a consciousness of different tones of the breath, helping to reconnect where chronic stress may lead to dissociation from the body.

See more about the links between breath, mindful and fluid movement, embodiment and self-care, and support for our defences and health by Charlotte Watts and Leonie Taylor in Yoga & Somatics for Immune & Respiratory Health (Singing Dragon 2022).

[1] Tosato et al, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2685272 (2007).

[2] Tan et al, www.nature.com/articles/S41392-020-0148-4 (2020)

[3] Campisi et a,l http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2011.09.001 (2011)

[4] Muntean, Hess, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2751531 (2009)

[5] Francheschi, Campisi, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23140366 (2014)

[6] Maggio et al, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16799139 (2006)

[7] Schöttker et al, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4678534 (2015)

[8] Maggio et al, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16799139 (2006)

[9] Dr Gabor Maté, The Myth of Normal (Vermillion, 2022)

[10] Dr Helen Lavretsky’s studies (UCLA), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30538/073 (2019)